Nevados de Ecuador y Quito Colonial, Ángel N. Bedoya Maruri, 1976

Wilhelm Reiss (June 13, 1838 – September 29, 1908), German geologist and explorer

On all sides without interruption, with tremendous noise, masses of snow rush down, piling up, in the extensive snow-capped that sends a long and mighty glacier westward and there it cascades from a vertical wall of almost 1,500 feet high and separating the floor of the crater (Plazapamba 4,300 m.) the marshy valley of Collanes. A part of the masses of ice, nearby, is torn and remains in rubble, in the little valley called «Pasuasu», at the foot of the rocks; another part precipitates in fragments and reaches the bottom as a coherent mass of ice. This glacier is the one that descends the most in Ecuador (4,028 m.)

Travels amongst the Great Andes of the Equator, Edward Whymper

At Penipe, the Jefo-politico was also the village tailor. He administered the law and mended trousers alternately; and created a favourable impression on five minutes' acquaintance, after declaring, according to the manner of the country, that his house was ours, by adding with uncommon frankness, “but, Sefior, I would recommend you not to go in-doors, for the fleas are numerous, and I think your Excellencies would be uncomfortable!”

Having obtained some information from him, we went on in the afternoon to a small hacienda called Candelaria, a miserably poor place, where nothing eatable could be had; and, being advised that mules could not be used much farther, negotiated transport with several young louts who were loafing about. For eighteenpence each per day, and food, four of them agreed to go to the end of their world—that is to say, to the head of the Valley of Collanes.

The master of this ragged team could hardly be distinguished from his men. He was a young fellow of three or four and twenty, who wore a tattered billycock hat, and no shoes or stockings. His very sad countenance probably had some connection with his obvious poverty. The farm could scarcely have been more bare of food. There was general want of everything—of yerba for the beasts, who had to go back for forage; for ourselves there was nothing; and food for the porters had to be fetched from a distance and sent up after us. The master volunteered to come on the same terms as his men, and to this I consented, on condition that he worked; though feeling that it was somewhat out of place to have one of the great landed proprietors of the country in my train.

This shoeless, stockingless, and almost sans-culottian youth claimed (I am informed, truly) to be the absolute owner of a princely domain. His land, he said, stretched from Candelaria to the Volcano Sangai. In the vicinity of the farm its boundaries were denned, “but elsewhere” (said, with a grand sweep of the hand) “it extended as far as you could go to the east.” At a moderate estimate, he owned three hundred square miles.

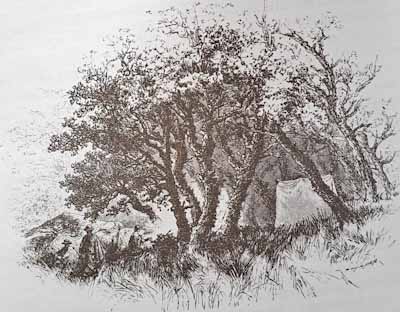

On the 17th of June, in two hours from the farm, we came to a patch of open ground in the middle of a forest, and the Master of Candelaria, who acted as guide, said mules could go no farther. Cevallos was left here with the animals, while we continued on foot, traversing at first a dense wood, which was impenetrable until three men with machetas had cleared a way, and then 800 very steep feet up the buttress of an alp. This brought us to a track winding, at a high elevation, along the northern side of the Valley of Collanes. At the latter part of the day we crossed from the right to the left bank of the valley, and encamped (at 12,540 feet) in a little patch of trees, close to the foot of the highest peak of Altar.

This valley of Collanes was well watered. Rain fell all the way, and during nearly the whole of the succeeding four days. Its slopes were adapted for grazing, deep with luxuriant grass, yet without a house, or hut, or sign of life. “Why are there no cattle here?” “No money,” replied the youth, gloomily. “Well,” said Jean-Antoine, “if / had this valley I would make a fortune.” When returning, we asked the Master if he would sell some of this land, pointing out a tract about six miles long by three or four broad—say twenty square miles, and he answered in the affirmative. “For how much?” He reflected a little, and said “one hundred pesos.” “For three hundred and fifty francs, Carrel, the land is yours!” It was just one farthing per acre. As he was so moderate, I thought of buying Altar for myself, and asked what he would take for the whole mountain. “No! no! he would not sell at any price.” “Why not?” He was reluctant to answer. “Why will you not sell Altar?” “Because there is much treasure there!”.

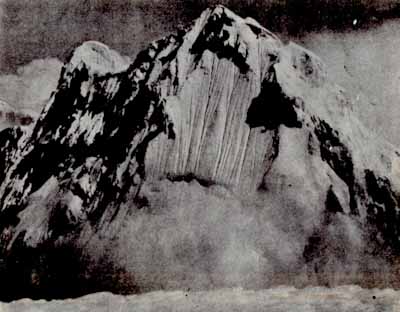

The treasures of Altar have yet to be discovered. The mountain is an extinct Volcano, having a crater in the form of a horse-shoe (larger than that of Cotopaxi), open towards the west; with an irregular rim, carrying some of the finest rock peaks in Ecuador. The culminating point is on the southern, and the second peak (which is only slightly inferior in elevation to the highest point) lies opposite to it on the northern side of the crater. The walls of the cirque are exceedingly rugged, with much snow, and the floor is occupied by a glacier, which is largely fed by falls from “hanging-glaciers” on the surrounding slopes and cliffs. The highest peak rises about 3500 feet above the apparent floor of the crater in cliffs as precipitous as the steepest part of the Eigher.

June 18. In Camp in the Valley of Collanes. Finding that we were nearly under the highest peak, and (from such glimpses as could be obtained through the clouds) that there was very little chance of an ascent being effected from the inside of the crater; I sent off J.-A. Carrel at 5.30 a.m. with two of the porters to examine the outside, and Louis with another to the outside of the second peak. Soon after mid-day Jean-Antoine returned, and reported unfavourably; and at 4 p.m. Louis came back, saying he had no view of the second summit during the whole day, but thought we could go as far as he had seen.1 Determined to shift camp to the north side of the mountain, outside the crater, if weather would permit. Min. temp. this night was 33°-5, and on the 17th, 29° Faht.

June 19. In Camp in the Valley of Collanes. High wind from the south-east nearly blew the tent over in the night, though it was well protected by trees. At daybreak there was a hard gale, and we were unable to move the camp. All the peaks of Altar were clouded, and much new snow had fallen on the lower crags. Same state of things continued all day. Wind dropped at night. Min. temp. again 33°'5 Faht.

Watched for the peaks all day. Saw that the highest point near its summit was guarded by pinnacles as steep as the Aiguille du Dru. The face towards the north carried several hangingglaciers. Frequently heard the roars of avalanches tumbling from them on to the glacier in the crater, the true bottom of which probably lies several hundred feet below the ice. This craterglacier, in advancing, falls over a steep wall of rock at the head of the Valley of Collanes, in a manner somewhat similar to the Tschingel Glacier in the Gasteren Thai. Some of the ice breaks away in slices, and is re-compacted at the base of the cliff, while part maintains the continuity of the upper plateau with the fallen and smashed fragments. This connecting link of glacier (seen in front) appears to descend almost vertically.

June 20. From Camp in the Valley of Collanes to Camp in the Valley of Naranjal. Broke up camp and left at 7.25 a.m.; crossed a small ridge running out of the north-west end of the crater, and descended into the Valley of Naranjal. Spied a big rock surrounded by small trees, and camped against it (13,053 feet). The Valley of Naranjal skirts the outside of Altar on the north. Was told that in six hours it would bring one to the village of Utunac. The second peak of Altar was almost exactly due East of camp.

In afternoon went with Jean-Antoine to the crest of the ridge on the north of our valley, to try to make out a route and for angles to fix our position. Descended after waiting two hours and seeing nothing. Great quantities of smoke rising from the bottom of our valley. Found camp nearly surrounded by flames—Louis Carrel having set fire to the grass to amuse himself. All hands had to work for an hour to beat out the flames and cut down bushes, and we narrowly escaped being burnt out. Continued windy and misty all night, and nothing could be seen. “This is going to be another Sara-urcu,” groaned Jean-Antoine, whose thoughts were in the Val Tournanche. Min. temp. in night 34' Faht.

June 21. From Camp in Valley of Naranjal to Penipe. Settled overnight to return to ltiobamba if there was no improvement in the weather. In morning, as before, fog right down to bottom of valley, with steady drizzle. Master of Candelaria said this was the regular thing, and gave no hope of improvement…

Revista Montaña, número 8, 1966

Dawn in Riobamba. I look out the window at the usual potbellied clouds that cover the sky and lick the moors of the Andes. The rather cold air seems to pierce me to the bone, and I feel overcome with a feeling of sadness. The city is located in a dusty valley where it almost never rains, at 2,800 m. Even more arid is the Chambo river basin, where the hot air that rises from the Amazon basin creates balanced conditions that prevent any rainfall in the valley. While in the heights that surround the city, especially in the eastern sector, the rain is abundant.

During the hours of the day, the Chimborazo is sometimes discovered and also the Tungurahua that shows us its steep and frozen cone. But only at sunset is there a chance that the veil of clouds will dissipate or lower. From the flat and already dark profile of the high moors, two very sharp and very clear peaks emerge in the serene sky. The snow on its rocks makes its sharp profile shine in the clear air. The icy scene is then warmed by the red hues of sunset. Those who know how to appreciate the spectacles of nature can hardly remain indifferent. The two points have a name: The Altar. it's evident that others have also felt the call upwards suggested by the mountain. Marino Tremonti June 1965.

American Alpine Club, Chimborazo and Monja Grande, by J. Richard Hechtel, 1969

El Altar is actually a single horseshoe-shaped mountain, whose highest point, El Obispo (17,457 feet) is at the southern end of the horseshoe, while El Canonigo (17,257 feet) is at the other. This horseshoe is divided into many peaks and gaps. Hans Meyer gave names to several summits in 1906. Along the ridge next to El Obispo is first Monja Grande and then Monja Chica (5,100 meters or 16,733 feet). The Tabernaculo (c. 17,400 feet) stands near the head of the horseshoe on the Canónigo's side. Apparently between these last two peaks lie two peaks climbed in 1939 by Hirtz, Ghiglione and Kühm. A German in Chile, who knew Kühm, told me that they had climbed two of the northern peaks called Pailacajas (5,070 and 5,100 meters) and this may help identify them.—Evelio Echevarria C.

In Ambato we immediately started talking about future plans. There was general agreement on El Altar, a group of beautiful, jagged 17,000-foot peaks about 15 miles east of Riobamba. We had seen photos of El Altar and knew that it offered the biggest challenge and hardest climb in the Ecuadorian Andes. After countless failed attempts, stretching back to Whymper, the highest peak of the group, El Obispo, was finally conquered by an Italian expedition in 1963. With the exception of El Canonigo, which was climbed by the same climbers two years later, most of the other peaks were intact.

On the afternoon of August 12 we left Ambato, our number reduced to four, as George Barnes had to return to the United States. In our rented jeep, now a little less crowded, we hoped to arrive in the afternoon at Hacienda Puelazo, the starting point for El Altar. We actually arrived the next morning after spending the night in the middle of nowhere. To our great surprise, we were immediately offered two pack animals and a muleteer. In a couple of hours we were back on the road. I don't know why the packer and his animals were in such a hurry. Despite being in good shape, we couldn't climb that fast. Fortunately, the horses' load slipped frequently and it took our packer and his son a while to reload them.

In the afternoon we arrived at the Vaquería, an indigenous grass hut, presumably built as in Inca times 500 years ago. It housed five dogs, three pigs, one billy goat, five people, and an unknown number of guinea pigs. They all seemed happy and healthy, free of ulcers and hypertension, and unaffected by television, traffic jams, and smog. They will need a lot of foreign help to develop all these things.

The next day, harder, the pack animals often went off the road but did not get hurt. Herb Hultgren slipped into a hidden creek and broke a rib. In the late afternoon we arrive at Machay, a small wet cave at 14,000 feet, our base camp for El Altar. There we met our new friend and partner, Shoichi Hinohara, who had just completed the fifth ascent of El Obispo with Ecuadorians under the leadership of Pablo Williams.

The next day, Herb's rib hurt so much that he went hiking with Pablo Williams. The next day, August 16, the rest of us, including Shoichi, moved to a higher camp in a glacial basin below the south face of El Obispo.

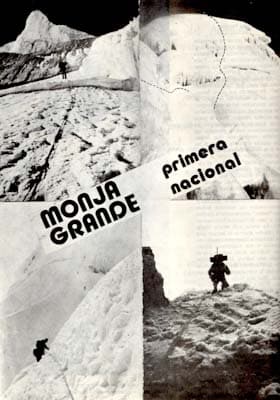

Despite poor visibility, Bill Ross and Margaret Young left camp shortly before noon the next day to reconnoitre the Monja Grande. Near El Obispo, it had not been climbed and its steep faces and wild ice falls looked imposing. Only at dusk did our companions return. In a daring race they had reached the top of Monja Grande.

Of course, Shoichi and I wanted to repeat this climb, but we had very little time left. Tomorrow our packer would meet us at Machay. It would be a long hard day, the climbing and the walking. Leaving camp at 7:30, we reached the top of Monja Grande in four hours. On several very steep and at least two extremely steep rope sections, our ice ax insurance had only a symbolic value. The descent was even harder as we didn't have enough rope and stakes to rappel. Back at High Camp at three o'clock we begin the long trek to Machay. Darkness fell and it began to rain. We continued on, slipping, tripping and falling under our heavy backpacks, wet and covered in mud. How miserable life can be! Wasn't that a human voice, the barking of a dog? There was the cave with our muleteer, his son and the dog. Suddenly, life was worth living again.

American Alpine Club. Sangay and Monja Chiquita and Tabernáculo, El Altar Group, by Peter Bednar, 1973

Tabernaculo 3 (to the left in clouds), Tabernaculo 2 and Tabernaculo 1, from the top of the Monja Chica

Our group was led by Erich Griessl and composed of Günter Hell, Rudolf Lettenmeier, Sepp Rieser and myself. We left Munich on December 26, 1970.

We reached the enormous horseshoe of El Altar in two days of approach. From the base camp at 4,450 m we used the first period of good weather on January 16 to make the first ascent of Monja Chica (5,080 m), climbing the west ridge very full of cornices. It took time for us to climb the 65-degree slopes of the northwest face of Tabernaculo I (5,180 m), which we did on January 19. This summit continues after the Monja Chica. After more bad weather, on January 26 we climbed Tabernaculo III (5,130m), up its 45-degree serac-covered southwest face. This is the third summit after Monja Chica.

Photo by Erich Griessl

Revista Montaña No. 12, 1980. Author: Luis Naranjo

Monja Grande, first national, 1978

THE IDEA arose a year ago on the occasion of a climb to the highest peak of the grandiose Altar massif. Indeed, we had carefully observed that slender and practically unknown white peak, located further east of the Obispo and separated from it by a perfectly defined hill. The immense crevices of the lower glacier and the steep channels that seemed to lead directly to the top were like a call to our adventurous spirit. We decided to accept the challenge...

LA Monja Grande (5,260 mts.) had been climbed only once before, by two foreign climbers, one American and one Japanese, as we had news. On this occasion, six Ecuadorians would try it: Roberto Fuentes, Hernán Reinoso, Mauricio Reinoso, Milton Moreno and Luis Naranjo, from the Climbing Group of the Colegio San Gabriel de Quito, and our good friend Marcos Serrano, from the Pablo Leiva Excursionist Group. We have all known each other for a long time because we have been working together at the AEAP Mountain School; We form a homogeneous group and we understand each other well. We don't have any technical data about the route or the objective problems that this ascent presents; These are all unknowns that we will have to solve as we go.

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 31, 1978. Farm Puelazo. Problems with the muleteers: they have only brought two mules, and to our claim they respond that in any case they will carry on their backs what the animals cannot. We cross the Inguisay River and arrive at the dairy; Shortly after, at the entrance of the Tiaco Chico valley, the unexpected happens: one of the mules rolls with all its load and it's not long before it kills itself. In the afternoon it starts to rain, the valley has turned into a swamp. We have never had so many mishaps in one day! Definitely, today we will not be able to reach the "Italian Camp", as planned. At 4.30 p.m. we see the Machay del Tiaco Chico; it's useless to pretend to move forward, we are tired of fighting with the animals, the weather and the terrain.

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 1. We advance slowly under the weight of our large backpacks. Little by little we are overcoming the hard slopes that precede the Negro Pacha blade; It hasn't stopped raining since dawn, bad weather ends up spoiling our character. At noon we arrive at the Italian Camp, the rain and the fog persist. The mountain is much snowier than last year, before arriving here we have already crossed some hills covered with abundant loose snow. We fail to see our target, and it's useless to venture onto the glacier without first examining it. We will have no choice but to spend the night here. Fortunately, in the afternoon the sky clears for a few minutes and we can more or less determine the route along the lower glacier. Tomorrow will be the day of the approach to the Monja Grande base.

THURSDAY 2. The alarm clock should have gone off at 4 in the morning, but it seems to have broken; In any case, it would have been in vain: outside it continues to snow and a very strong wind is blowing. I leave the store to take a look, everything is discouraging. At eight o'clock nothing has changed, anyway we are going to try to leave. We prepare the equipment, load the backpacks and enter the fog.

Slowly we descend through the rocks until we reach the snowfields that lead to the base of the lower glacier; the snow is loose and quite wet, the going becomes heavy. Four hours later we are at the foot of the rocky blade that last year led us to the summit of El Obispo; I clearly remember the bivouacs on the edge of this ridge... Despite everything —I tell myself— the Altar hasn't treated us too harshly, let's hope the same thing happens this time...

< We have crossed several cracks, and we have barely advanced eight hundred meters from the base of the Obispo's ridge, when we decided to set up camp. Once inside the tents, we take care of our wet clothes. Personally, my feet are wet, it seems my old leggings are beginning to fail, they never gave me any problems... until today. I get into my sleeping bag with almost everything on, it's the only thing I can do.At dusk the mountain clears; To tell the truth, we are much closer than we imagined: we only have 900 meters left. to the base, but it's highly avalanche-prone terrain; the same happens with the first gutter, whose beginning is marked by an immense rhyme. We quickly mapped out three possible routes of ascent; the one that seems most feasible would lead us directly to the hill between the Obispo and the Big Monja. Although from there it presents some hanging cornices towards the side of the Caldera, we think that we will be able to advance to the top. Anyway, tomorrow will be the day...

FRIDAY 3rd. We leave the camp at 3 in the morning, and after a short stretch of glacier we get through the debris of recent avalanches; I am horrified to think of the devastating force of these blocks of ice rushing down the flanks of the mountain and sweeping everything in their path...!

A crack, it's very wide and deep. There is only one bridge, but it seems unsafe. In vain I try to discover another passage, I can only distinguish the gloomy darkness of its depths. There is no other solution, let's try it. I advance cautiously, suddenly the surface layer of ice breaks, my ice ax sinks to the cross and me to the knees. I continue dragging myself, Roberto encourages me; I finally reach the opposite shore. My companions repeat the maneuver one by one. The stars are fading, as are our flashlights...

At dawn we are in the rimaya, we cross it through the avalanche cone and enter the first large gutter. We then cross diagonally to a side corridor whose slope forces us to use the front ends of the crampons. A length of rope deposits us on a small ridge somewhat away from the hill that precedes the last large gutter. We dodged a crack and climbed onto the ledges of the hill, from where we could see, on the other side of the Caldera, the imposing southern walls of the Canonigo and the Frailes. Very carefully we move to the right; the sun has already beaten down on the icy slopes and the snow will begin to soften soon. it's necessary to move quickly and safely.

We stand under the last large gutter, attached to the seracs on the left; the climb becomes slow because we go in groups of three. In the last lengths the inclination is accentuated, our breathing is gasping, the result of fatigue and emotion: we are very close to our goal. A few more ice ax strokes and... The summit! We are on the cusp of the Monja Grande!

It's 9:30 a.m., joy mixed with wonder. The view is breathtaking and the imagination runs wild. Below, at the bottom of the Caldera, the Amarilla lagoon, almost a thousand meters of difference in level separate us from it! Hugs and pictures.

IT'S TIME TO GO DOWN. Very carefully we climbed down the large gutter, which due to the heat now constitutes a constant danger. This time it takes us much longer, it seems as if it will never end.

Our tensions loosen a bit when we reach the pass and we all meet to decide the best way to go down. We will make an attempt to rappel down directly to the first large gutter, thus avoiding the passage of the dangerous ledges. We install the rope and I begin to descend; Twenty meters below I stop, impossible to continue, the risk is too great. To continue, we would have to. rappel down to an isolated block of ice that offers no guarantee of stability; it's better to retrace our steps, so we begin the crossing of the blessed cornices.

At each step there is suspicion, fear; each length of rope is a mystery: will it withstand the snow? No one speaks a word, all our attention is fixed on the movements we make. We don't stop, we know that our safety is there, on the other side of that row of footprints in the broken snow. Sometimes, a piece of ice breaks off and falls down the vertiginous slide of the large gutter below us.

At the end of the ledges we install a rappel that leaves us on the ridge that crowns the side corridor . Two new rappels and the most serious is left behind. Calm returns to our spirits and a smile of satisfaction erases the tension from our faces. What is missing no longer worries us.

Slowness and tiredness mix with our joy; an inner experience enlivens the monotonous march on the lower glacier. The sunset, the mountain, our camp, the rest...

Revista Montaña No. 12, 1980. Author: Luis Naranjo

After eight days of fighting in the mountains, the joint expedition of the "San Gabriel" and "Pablo Leiva" clubs reached the summits of "El Canónigo" and "Fraile Occidental" in the "El Altar" massif.

The desire to conquer the last virgin summit in El Altar led us to set up an expedition of nine mountaineers, who, working together, would try to explore the moors and glaciers that protect the steep slopes of the mountain.Our main objective , El Fraile Occidental, inviolate and mysterious summit located on the northeast flank of the caldera between the Grande and Central Frailes.Occasion to be united in a new company.

Leaving from Quito on Saturday September 22 in the morning, and traveling the road that leads to Penipe and Candelaria, we have managed to hire in this town the two muleteers and four mules that will help us transport the loads through the moors of the region. At night we talked with Ramón Gómez, they came from doing El Canónigo: and how is the weather? Acceptable; And the climbing? Hard, very hard, a bivouac on the rocks; congratulations!, congratulations!

APPROACH

The weather is unbeatable and we are convinced of the victory, Candelaria and Releche are behind while we shorten the distance on the road towards Cerros Negros; the majesty of the mountain comforts us during the first day of march whose day ends with the arrival at Machay that our muleteers know as "Rancho de Cerros Negros", from where the North flank of the Canónigo is contemplated, impressive difference in level, about 1000 meters .

The next day of approach is diluted crossing the Cerros Negros swamp; we have distributed the load because it's impossible for the mules to manage to cross this kind of terrain; the help that the muleteers gave us when carrying all the food ended at 11 in the morning; From now on the march becomes painful, I calculate that the backpacks must be weighing about 60 pounds, and what is worse, it has started to rain. At 4 in the afternoon we are forced to install an emergency camp after an hour of having endured the storm; That's enough for today, we're practically under the Canonigo.

BLOCKED

The weather is against it, the blizzard has blown all night and wreaked havoc about the tents; don't even think about going out today, if there hasn't been a second of calm; a lost day is just a lost day, tomorrow we will recover it; we plan and comfort each other.

The weather hasn't improved; We have already had two full days of storm and the time that we have left available is reduced to the maximum; the mood and the possibilities run out, I think there is no hope. After talking for a long time, we decided to take urgent measures, tomorrow Thursday will be the key day, if God helps us something can be done. it's important to ensure the conquest of some summit; we know from the references that we are still far from the los Frailes glacier and the chances of achieving our goal are quite remote. We decided to split the expedition; We will choose a safe rope of two people to make the attempt to climb the Canonigo, while a group of six people will try to cross the immense and cracked glacier that separates us from the rocky ridge that descends from the Fraile Grande, from where we hope to see the remaining Frailes. among which is ours; if the weather allows us we will try the climb; if not, we will have obtained good data from the approach, which will be useful to us next time.

THE ASSAULT

Thursday morning has been disastrous, someone has even proposed withdrawal and while we wait it begins to clear up; it's noon and we take the opportunity to prepare things, we'll leave as soon as possible as we had planned.

Agustín Serrano says goodbye to us in the camp, take care! They are emotional scenes; Through the mist and at a slow pace our colleagues Ramiro Návarrete and Marcos Serrano walk away, we will not know about them until the company is finished; success or failure will only be known when everything is over.

We, in silence and meditating, try to gain altitude before going up the glacier; it has begun to snow but it's in vain, nothing can stop us now that the adventure has begun.

A ten-meter gutter carved into the seracs puts us on the glacier that impatiently awaits the start of our journey. From the beginning we took accounts of the land; the compass marks the course and we cautiously begin to dodge the labyrinth of cracks; We have sometimes fallen into their traps, this slows down the march but doesn't break the spirit; slowly we approach the ridge of the Fraile Grande: the glacier climbs over it at a certain point offering us a step that we use to climb on the spur; once on it, we realize the existence of a small snowfield that limits a new ridge, a fork of the main ridge that descends from the summit. it's quite late when we manage to reach it and the fog continues thick over the environment, the weather has not favored us; at first we will stay here to bivouac... Suddenly everything begins to change, the strong gusts of wind blow away the fog that prevents us from looking and an imposing spectacle remains before us: this fills us with joy, we are closer than we we thought, in front they rise: the Oriental Fraile with its sharp edge that reaches the summit; the Central Fraile, huge and full of cornices that form spooky “cobs” of ice; and our long-awaited Western Fraile, beautiful peak of rock and ice: we have already drawn routes for him and we choose the most feasible, but now we must hurry if we want to reach the base of the mountain; in one more hour we must install the bivouac site; Tired and panting, we walk the stretches of glacier that lead us to the very base of the Fraile...

The night turns cold, we have sung and talked until we fell asleep; a thousand memories in the mind: family, mountain days, strong climbs, camping joys... the night is quite calm.

Before dawn we begin to prepare for the assault, we go out in two ropes , I am in front of the first, behind Danny Moreno and closing Fernando Jaramillo; on the other string, Hernán Reinoso, Mauricio Reinoso and Milton Moreno; I know we will be slow, but we will be safe. The approach steps warm up the stiff muscles and already at the base we try to gain height. The first pitches are touring, a 60 meter zig zag places us under a large gutter; climbing becomes unsafe, we work on ice "crusts" that break as we go; 100 meters of gutter are endless, at the end of it rises the last wall before the hill that leads to the summit; there are 40 more meters of extremely “fine” climbing. The force applied on the boot must form only one step, kicking hard crumbles the ice sheet, the tools aren'thing but psychological insurance; step by step difficulties are overcome, I have to climb the hill to install a fixed rope, success is in sight...

We have finished the climb and it's already noon, our backpacks are left in the hill, at the top just us: Hernán, Mauricio, Danny, Fernando, Milton and Lucho... how do we baptize it? I don't know, I don't know, we'll think about it; joy, tears, friendship; again united in a summit.

We thank God and hope he protects us on the descent; we have decided to “abandon” whatever it's, the important thing is to go down quickly and safely; With the first rappel installed, we reach the cone of the gutter from where we climb down the walls, installing two more rappels. The routes are long, but that is the only way to save time. In the middle of the afternoon we are back at the base, now we have succeeded.

We gather our things from the bivouac and hurry back to the camp. The tracks on the glacier are intact, the cracks we know by heart, we're on our way home when it starts to get dark, suddenly... look there! Upstairs, in the Canonigo! It's them! Yes, it's them! ; Ramiro and Marcos are abseiling, we can see them, but they are very high; we're almost done, they're still fighting...

Revista Montaña No. 14, 1983. Author: Santiago Palacios

SW Wall of the Tabernaculo, seen from the camp on the hill

Attracted by the beauty of this mountain we decided to undertake one more expedition to the Altar; this time it would be the Tabernaculo. A pyramid of rock and ice that is located in the center of the semicircle of the massif. In addition, we were motivated by the illusion of making his first absolute ascent.

On December 26, 1981, Roberto Fuentes (Chief of Expedition), Mauricio Reinoso, Hernán Reinoso, Fabián Cáceres, Antonio Palma, Fabián Almeida, Iván Aleaga and myself; We left for "Candelaria" where, as on previous occasions, we enjoyed the good treatment and friendly hospitality that the residents of this bucolic and beautiful place gave us.

The next day began early for us, at 6 o'clock. In the morning we go to Hacienda Releche from where we depart towards the valley of the Collanes River. We had spoken the day before with Don Miguel Carrasco, who, like him, would always carry the load for us. This time he was accompanied by his two sons: Marcelo and Miguel, his niece Hortensia; two dogs and five mules. After a calm march and without much effort we arrived at the Collanes gate, to where Don Miguel accompanied us. It was one in the afternoon and we had our first lunch on the mountain; a piece of salami, cheese and pepper; a few biscuits and abundant liquids, they were scarce at that time but it had to be that way.

At two in the afternoon we left with the intention of reaching the Mandur Lagoon, for which we had to go up the southern slope of Collanes. At five in the afternoon we were halfway through the road and also very tired, so we had to set up our first camp.

At 9 in the morning on Monday 28, we broke camp. On this day we would try to reach the base of the Tabernaculo, but we made a mistake in calculating the time because at two in the afternoon we were just above the Mandur Lagoon near the Obispo Glacier. The weather was bad, we were cold and wet and decided to set up a second camp (4,500m).

On Tuesday 29, the weather was still bad, but we had to get to the base of the Tabernaculo anyway. We begin a new stage in the approach over ice and crevasses, having to overcome the Obispo, Monja Grande and Monja Chica glaciers. We continue united in a single rope, keeping our proper distance, an extremely exhausting march due to the weight of the backpacks and the constant tension that crossing glaciers requires, but calm because of the security with which Mauricio led the journey.

Our effort was fully compensated when we found ourselves in a wonderful environment: to our left the Obispo and the Monja Grande stood haughtily; to the right and between clouds the smoky Sangay, and the eastern foothills of the rest of the massif; closer to us is the Blue Lagoon, at the foot of the glaciers.

We did not know exactly the route to reach the base of the Tabernaculo, but fortunately, at two in the afternoon, we found a series of banners left by a group of climbers from the Army Polytechnic School in previous days. The ESPE group had left before Christmas in pursuit of the same goal.

The weather had improved during the afternoon and the mountain looked even more beautiful and attractive. Following the tracks, we crossed the Monja Chica glacier until we reached its southeastern hill, from where we were able to see the Tabernaculo for the first time and, shortly after, we came across the ESPE camp, for whom neither time nor luck had favored them, and until then day they failed to achieve their goal. At six in the afternoon we set up camp III (4,870 m), on the edge of the caldera, under the northeast face of Monja Chica. From there we could contemplate the beauty of the mountain in each of its peaks, from the Canonigo to the Obispo. That afternoon we carefully studied the mountain, at first we thought that there should be an easier route along the eastern face, with which we would avoid the southern wall that appeared to us as the direct and clear but very exposed route. At that moment we decided that a team would attack the directisima through the southern wall and the other two teams would explore the eastern face in search of a more feasible route, and Antonio and Iván would have to stay in the camp. The peaceful afternoon was an invitation to meditation, the ensemble was incredible, a thousand dreams disturbed us...

On Wednesday 30 we tried to reach the summit, and at nine o'clock in the morning we left three groups in pursuit of it, having changed the plans for the Interior day. Now we would all go along the south wall; Mauricio and Roberto, Fabián Almeida and Fabián Cáceres, Hernán Reinoso and I. We had full gear to get over the ice ramp and a likely rock step, plus we were prepared to bivouac if necessary. We were in good technical and physical condition because at 9:30 in the morning we began to climb, progressing alternately in each rope and using the ice screws to secure. The ascent was slow and exhausting for the first 100 meters until reaching the rock chimney in the middle of the wall approximately, each movement required concentration and effort. We had gained height in a short time because the slope was almost extreme. After overcoming the rock chimney we were already very close to the summit. With three lengths of rope we reached the edge, after the funnel after the rock pass, we were a few meters from the summit, the last pass was a small wall of rock and very vertical ice. At one in the afternoon Mauricio and Roberto were already at the highest summit (5,090 m.) and half an hour later all of us. We felt very happy and satisfied, all the effort was justified, it was a triumph more for Ecuadorian Andinism and in a very special way for our beloved Ascensionismo Group. Half an hour later we began the descent, for which we used ice anchors and after 5 rappels we found ourselves at the foot of the wall. As we descended, the mountain cleared and we clearly appreciated the impressive air route we had followed. On the Collado, we observed our tiny camp, the repressed tension along with the triumph achieved exploded in an overflowing joy. Everything had turned out well, thank God.

On Thursday 31 we started our return, the march, although extremely exhausting, made us gain a day, we traveled from the base of the Tabernaculo to the door de Collanes, it was eight o'clock at night when I arrived. A new year was approaching and as sometimes it would no longer be a family celebration for us, but rather a supportive embrace in sacrifice, paid for with the joy of this new triumph: 8 climbers, 8 brothers, at El Altar.

Despite our enthusiasm to receive it, fatigue overcame us and we fell asleep. The next day, in the tranquility of the valley, we only had to prepare our backpacks for the return, and feed ourselves with the last rations that were left over, which without being a banquet brought us the special memory of the people who with much love helped us to prepare them.

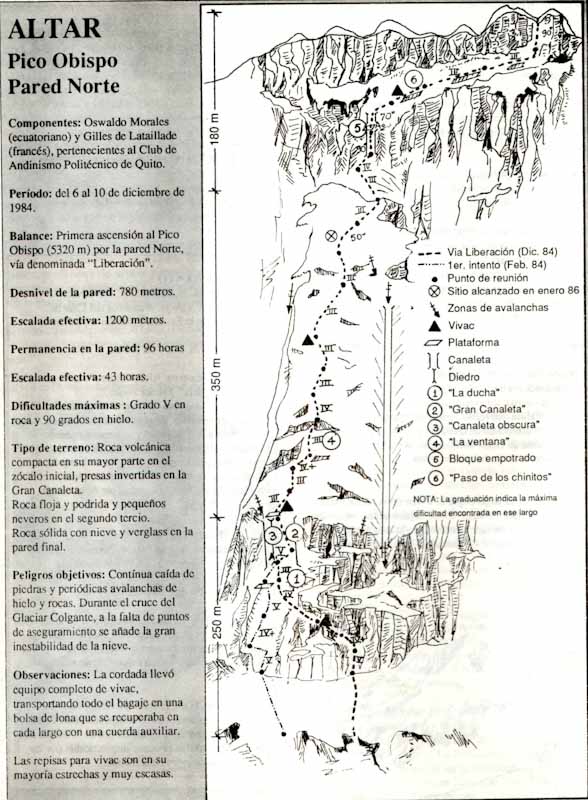

Revista Montaña No. 16, 1989. Author: Gilles de Lataillade

North Face of the Obispo

Chronology of a dream, by Iván Vallejo

I don't know if I was lucky or unlucky, while we were doing the rope lengths on the "edge of the Sun" with my Pana Giles, of being at the first moment in which the idea of climbing El Obispo through the caldera was conceived.

The conceived idea was gestating week after week and every Wednesday in session we saw what could be done in in terms of necessary arrangements and hustle and bustle, to keep that conception alive.

February 1984: The temptation comes to an end and Giles, acolyted by another "frog", decides on the first serious recognition of the wall. This begins on the side of a large spur at the foot of the North. I remember that when he came back, they told me about “scarce prey”, “bad rock”, “V here, V beyond”, etc. etc.

August 1984: Between prying ears and prudish looks, in a short conversation, one of those that can only be carried on while traveling comfortably on a bus full of the VICENTINA-EL RECREO brand, stretching no further to hold his neck so as not to suffocate and to be able to at least look at the eyes of the interlocutor, Oswaldo Leiva told me that he had been in the North with a "ball" of people and equipment, and at the same time he informed me of the accident suffered by Jorge and its sports combo. Oh wow!

Article, by the Spanish Pedro Alonso

We arrived at base camp at night full of joy. The a priori terrible first plinth was finished with 20 meters to go and it had only taken us 3 hours to equip it with fixed ropes. The possibility of victory became tangible for the first time and not an unreal dream.

August 6 dawned splendidly. These Ecuadorians are lucky, I thought to myself. The 3 of the first day attacked the wall again, leaving Kiki in the advanced field. It was 8 at night and the Ecuadorians still hadn't come down.

-But what a joke they're doing, if they only had 20 meters left.

-Would the unlucky ones have stayed to attack tomorrow and get ahead of us?

A quick look at their tents.

-No, no, here they have the bags so they have to go down.

We were already a bit uneasy having coffee with some English people who had come to visit us, when Carlos, startled, he yelled at us:

-iLuces! There are lights on the wall!

Our blood ran cold, shotgunned we went out to see the flashing lights.

-Three dots and three dashes. "It's a sign of danger" -said the Englishman-.

The truth is that something bad was happening, otherwise there shouldn't have been fixed lights on the wall at that time.

Carlos and Jorge quickly packed their backpack and left with the intention of finding out what was going on. Meanwhile, I was trying to get along with the English, so we sought the help of Marco Cruz, who was accompanying a group of clients from the French Alpine Club. While we talked to Marco, Kiki, Oswaldo, Carlos and Jorge appeared, some of them had been going up and others going down. They told us:

-When we got to where you left the rope, we started climbing and Rómulo, already reaching the top of the ridge, a block fell off, flying about 10 or 15 meters, he hit the wall with his head , breaking his helmet without anything happening to him. The stone fell and hit Jorge Anhalzer in the left leg, fracturing it.

The next day Jorge went up to get the ice axes and crampons that we had left in the material deposit and Alfredo and Carlos began the approach towards the Púlpito , following them. At one hour, the two of us, in order to attack this spur, traversed through snow from left to right, up to a corridor on the left flank of the spur that, after an apparently easy chimney, would take us to the edge and to a considerable height. It was not like that, the chimney was covered with pure ice and we had to force between Alfredo and me a length of V almost without insurance through the front left wall of the gutter, we took a long time, at 12 o'clock the weather worsened, we had to rappel down to the base camp.

On the 16th, already without food, we decided to leave and it was still raining, it was exasperating, 10 days in a row of bad weather.

We would still return again on the 26th Jorge Vicens, Mauricio Reinoso and me. Our flight to Spain was on the 31st, and we had just the right time. We arrived at Collanes and our misfortune and anger increased. After a splendid week, the weather took a turn for the worse on our arrival, we were greeted by rain and left raining after a night at Collanes base camp.

The mountain said No! Gone are the illusions but a great satisfaction could not be taken away from us: seeing Jorge Anhalzer content and happy, his leg, according to the doctors, would fit perfectly, without the need for surgical intervention.

Chronology of a dream, by Iván Vallejo

December 1984: What are they leaving? ...They go!, Giles and Oswaldo to the North. They were kind enough to extend the invitation to me, but due to endless complications and messes from the damn job, it was impossible for me to join my pair of friends. You have to say NO! And then one is left with a mixture of frustration and anger, waiting for the days to pass and the torment of uncertainty to know how it went to end.

The conceived idea was now in labor pains.

Ecuador, North face and theology, by Gilles de Lataillade

I had dreamed of this wall for a year and had often thought of the summit. I imagined an arrival in broad daylight, taking a handful of snow in my hands and melting it in my mouth. I imagined hugging all my teammates while congratulating each other on our success.

Things hadn't gone that way. Sure, we had climbed the Obispo's North Face and it was as wild and difficult as we imagined. It was going to provoke a small revolution in the Ecuadorian mountain range. Among those who had seen it, many said it was unclimbable: 800 m high, cut by two vertical walls of 200 m, one below, the second at the exit. A rotten rock and definitely bad snow.

We had also climbed “alpine style”. It took us four bivouacs to reach the summit ridge. The success had been complete because we had climbed directly to the summit.

In the end, my account of the expedition will be very similar to the one I imagined since I dreamed of this wall. But instead of the story full of life that I had been inventing for a year, now I only find an empty text, an uninteresting succession of technical steps, anecdotes and bivouacs.

However, it was so that this dream that we had left, Oswaldo and I, may come true, even though the second group had withdrawn and lost the "sherpas", some friends who had to help us load. Perhaps there was a bit of unconsciousness or lack of sleep after two days of preparation in Riobamba.

Wednesday, December 6 in the morning, we had run into Don Pancho, one of the inhabitants of the town of Candelaria, who best knew the surroundings of the mountain. His son had accompanied us to the foot of the "Cauldron", the gigantic circus formed by the summits of the Altar.

Great spectacle whose significance appeared to us in its entirety: all these walls were virgins; Of course, all the peaks had already been conquered, but never from inside the circus. However, their “normal” routes were considered the most difficult in the country. These names are magical for Ecuadorian climbers: Canonigo, Frailes, Tabernaculo, Monjas. And we thought of attacking this wall at the point where it's highest, the lead of the highest summit of the Altar. The Obispo.

Thursday morning we had abandoned our tent that was later to serve Don Pancho and began our slow ascent to the foot of the wall. With some pleasure I realized that he recognized very well all the details of the passage when he had not been back here for almost ten months.

In February, with Alain le Mouellic, a Frenchman passing through Quito, we had made the first serious attempt for this face. We had barely missed thirty meters to get out of the first wall. But above all, we lacked a lot of preparation. Even if the weather hadn't worsened, we would have had to go down.

For the Ecuadorians the warning had been serious. How to let yourself be robbed of the route by two “frogs” even though one of them is a member of a Quito mountaineering club. At the beginning of August a strong expedition attacked the wall, but luck was not on their side and just a few meters above the point where we had arrived in February, a heavy block of rotten rock came loose, causing an accident. Jorge Anhalzer, the leader of the expedition, left with an open fracture in his leg and the group had to leave after a delicate rescue operation.

So we were starting the third attempt. With the backpacks we were carrying, the simple fact of reaching the foot of the wall was no longer a small thing. I was beginning to think that the conditions were a little worse than on my first attempt with Alain.

But a good surprise awaited us at the foot of the wall, the previous expedition had left fixed ropes up to that famous pitch of rope where the first two attempts had left off. I started attacking the first pitch, helping myself with a jumar, but very carefully, as these ropes had been in place for more than four months. We had reached the foot of the wall at one in the afternoon and it was already six, after two lengths of jumar and having pulled the backpacks; it was time to think about bivouacing.

The next day, a few pitches higher, we finally reached the key problem of this first part. I went out without a backpack on this steep and easily fragmentable rock. After about ten meters I recognized the impressive yellow mark that indicated the place occupied by the rock that caused Jorge Anhalzer's accident. Technically, the climb was delicate, without more, but what undoubtedly ensured "atmosphere" was the almost non-existence of serious insurance points. The fireplace session was mixed steep. Protection became totally impossible. The typical step where one spends his accounts with the afterlife.

With his right hand he grabbed some deversant prey, those that were left over after "cleaning". To the left I was poking at the thin layer of snow with my ice ax hammer to discover a vein of ice. Every three or four meters driving a peg left between two wobbly stones gave me the courage to continue climbing a few more meters.

The rock got steeper and the gutter wider, until it became practicable. I followed it for a few meters until I reached the end of the rope on a rock that I hugged before stuffing it with pegs and nuts. I hoisted the backpacks and Oswaldo went up, recovering the material left on this pitch by the three previous expeditions.

Above us the gutter led to the second part of the wall: a large slope in mixed that ended in a suspended glacier at the foot of the terminal wall.

A little further up was where we set up our second bivouac. The type of organization adopted forced us to progress very slowly. We had gone out with very heavy backpacks and it was impossible to climb carrying such a weight. For this reason we had brought a canvas bag in which we pulled all the bivouac equipment. it's very common for this fabric cover to get caught and it's not uncommon to lose an hour to unhook it, and it's worth knowing that in Ecuador the days are never long. At any time of the year the day hardly lasts more than twelve hours, every afternoon we had to look for a bivouac “In extremis”.

On the fourth day, at noon we were in top shape. After the difficulties of the second day, the climb had become calmer. We were now at the foot of the great terminal wall. We had good hope because we thought we had found an itinerary. We were happy, three bivouacs had already passed and they had become the most natural thing in the world. We got better and better organized. Life in the mountains is a simple thing: climb during the day, look for a bivouac place when night comes, prepare food and sleep. It was what we had been doing for five days. Of course there are small problems: melting snow for food and drink, protecting yourself as best you can from the cold; sometimes the bivouac becomes uncomfortable, the sleeping bag slips on the platform and the ropes that support us cruelly penetrate the flesh. Every morning you have to shake the ice-covered sleeping bags.

But, after all, these inconveniences are part of the game. They force us to know our limits and to make full use of our reserves and experiences. They are, in this way, a source of certain satisfaction, and undoubtedly bring with them the security of an unparalleled tranquility.

That day all the elements were gathered to make us feel happy. We had already attacked the problematic part of the wall and we had mentally drawn the itinerary that would take us to the summit, the climb was aerial and beautiful, hard enough for all our attention to be with it. The main difficulties were in the irregular quality of the rock. The snow, although quite steep, sank down a lot. Every time I started the ascent again I felt light and confident, however every time Oswaldo hoisted himself up with his jumar, I looked shuddering at those bits of metal that were the only supports for our tiny silhouettes almost at the top of the enormous wall .

We were surprised at night when he was just passing a block that obstructed the chimney. It was seven o'clock in the evening. Oswaldo asked me to stop for a moment to use the radio that, regularly, at 6 in the morning and at 7 at night, put us in touch with Don Pancho.

When I began the ascent, the darkness she was starting to get upset. Luckily I only had a few meters to go. The cycle was clear and the moon was beginning to peek out, promising a very clear night.

The darkness was complete when Oswaldo attacked this last pitch. It was when I realized that he seemed very tired, he stopped several times telling me that he couldn't take it anymore. It must be said that the poor guy, from the beginning of the afternoon, hoisted himself up with a jumar and carried his backpack while I, the leader's privilege, climbed without a backpack since we pulled it after each pitch. When he finally reached the meeting point, he could barely stand and mumbled incomprehensible words. In the place where we were we could not even think about making a bivouac. The snow was too loose to trim a platform and we couldn't even sit down. He was beginning to fear having to spend the night there. We were already at 5,200 meters and the nights were getting colder, the day had been tiring and we needed to rest at all costs.

Above us the chimney rose sharply and was bordered by two practically vertical walls a few meters high. So there was a mixed slope of about ten meters above us. I decided to climb up to this point hoping to find a platform. I felt at this point extremely lucid and physically fit. In the dark I climbed a few meters of bad snow and very steep and was relieved to discover that there was a small overhang at the foot of the terminal wall that left a narrow but precious platform below.

I installed a fixed rope in place and invited Oswaldo to make the last effort of the day. He, meanwhile, had taken advantage of the stop to recover. I only had to go down these ten meters to recover the backpack, unequip the meeting point and go back up to prepare what without a doubt would be our last bivouac. Discounting Oswaldo's little blank moment, he found that the day had been good and he was already enjoying himself thinking about the next day's start that was already within reach, which was going to mean victory and the opening of the most country difficult. Everything had been as good as it could be and we could congratulate each other on how things were going.

A slight creaking noise interrupted my thoughts. At the same moment I heard Oswaldo scream, I saw the avalanche rushing towards me and I hit the wall as hard as possible.

At a moment like this time stops, there is only death that falls, strikes, tears off, tries to move the body away from the wall, pass over it with all its weight and draw it into the abyss. Life is summed up in a single and totally physical point: merging with the wall, pulling that pin as hard as possible.

The noise of the avalanche disappeared towards the bottom of the immense crater, leaving room for an impressive silence. “Gilles, are you okay?”.

Oswaldo's voice reached me at the same time clear and wavering like a candle flame. And what could I answer? He wasn't even sure he was really alive, I instinctively felt his arms and legs. Luckily the helmet and backpack had protected me. Only my shoulders and arms ached. I replied that he was fine. I recovered all the material except the pegs because he didn't have the strength to start. I went up as soon as possible to the refuge that this providential bivouac offered me.

He was collapsed. Oswaldo fully recovered now, he prepared water and put a soup to heat.

This pitch had to be the last. The gutter headed to the left and got steeper. The last three meters were completely vertical. I stuck a good ice screw and launched, impatient. I couldn't help but cry out with joy: in front of me the slope of snow was calmly descending and the landscape extended to infinity to the south. To my right, about ten meters at most, stood the summit of Obispo . A few minutes later Oswaldo arrived. When I saw him end up on this summit I wanted to hug him. Without him none of this would have been possible. I will never be able to explain why, but there was a link between this mountain and me. She had, so to speak, fallen in love with her and everyone at the "Polytechnic" Climbing Club had been able to verify it. But few knew that, for love of the Ecuadorian mountains, they would have followed me in these conditions.

He had done it. And now he was here, calmly retrieving the rope, looking approvingly and somewhat amusedly at the summit, the object of so much effort.

And here was, perhaps, our victory. What at first seemed impossible, we had achieved. We had come out to violate the limits of the unknown and risky, all for this summit. Plus, if we were here, wouldn't it be simply because it was humanly possible? We were no Messner, no Edlinger, not even much less. We had not overcome any infernal wall. We were not at an inviolable summit. We had only overcome our own limits, we had fought our own doubts.

And that is what the entire landscape cried out for. The neighboring peaks, the Yellow Lagoon, a thousand meters below, the sea of clouds above the Amazon jungle told us “Look, I haven't moved, nothing has changed. Even if you weren't here, even if you hadn't risked your life under the avalanche, we'd still be here, in the same place.”

Is the story over yet? Unfortunately not, because the rest is just a bad dream and an unpleasant memory. We had spent a lot of time on the summit and were surprised at night during the descent. The tension had relapsed and we were now feeling the effects of the hardships of these last few days: lack of water and sleep in particular. We were aware of our state of exhaustion. It had already been five full days since we had left the comfort of the tent.

However, there were only a few hours left before we met Don Pancho and could finally sleep under a roof. All that was missing was a rappel and we would be calm. But here was when the accident occurred.

We had lost our only headlamp and Oswaldo had found a metal ring left there, when descending, by the last rope that Obispo had climbed by the normal route. .

A short time later watching Oswaldo go down when, suddenly, he separated from the wall and fell like a mass, without a cry, without a sound.

The night, the fatigue, my daze were such that I couldn't immediately understand what was happening. For a few seconds that seemed like a century, there was no sound to break the heavy silence other than my cracking voice. Oswaldo finally answered. As if in a dream, I helped him out of the crack where he had fallen. At the end of the rope, the ring that had come loose.

Despite his broken nose and his face bloodied we began to head towards the Italian Camp where Don Pancho was waiting for us, at the end of the path there was a rock barrier where it was necessary to climb a bit. We left the canvas bag, the rope, the carabiners and everything that was too heavy. You would have to come back the next day to pick it up. I carried Oswaldo's backpack and, guided by the voice and the distant flashlight of Don Pancho, we left to make the last effort in the frozen night of the Altar.

A week later I took the plane back to France leaving this Ecuador where he left so many memories. We had not found a name for the route. Suddenly an image came to me. It would be called: “Liberation Route”.

Revista Montaña No. 16, 1989. Author: Luis Naranjo

South face of the Canonigo and Fraile Grande from the Central Fraile

CHRONICLE OF A DAY ON THE SOUTH FACE OF CANONIGO

It took only a fraction of a second to realize that from now on we would have to face the catastrophe. Never the first thought is death, you just know that suddenly everything will be complicated. Simultaneously, that feeling that nothing is holding you, is like when I was thrown down the slide as a child, the vertiginous descent made my stomach rise into my throat; but this time it was not a game, obviously the rope had broken and I was falling into the void.

Then the first blow... nothing is felt, then the helmet crashing against the rocks emits a strident sound that It has remained engraved in me like those childhood nightmares, finally the tough guy... that terrible tough guy who tells you “you've come this far”; it's that you are caught by a hair and the slightest movement could help you cover the remaining 400 meters to reach the base of the wall that I see very well, because when you are hanging with your head down you can see very well the base of the wall.

I don't know how long we were silent, neither of us dared to say anything, -Mauricio has confessed to me that he was afraid of not receiving an answer-, that's why he remained silent And I didn't even want to breathe. I slowly turned my head to the right and managed to make out a pin, stretched out my arm and grabbed the ring.

-!Mauricio!,...!Mauricio!...am I insured?

I heard the answer from afar.

!Yes...you're sure!

With fear I began to move without letting go of the ring; after kicking for a while I managed to straighten up and secured myself with a carabiner to the pin that fate put in my face. It was like muffled, I didn't feel pain but everything looked blurry. It made me angry because I knew that the mistake was ours; almost all accidents are the fault of the climber because the mountain doesn't know that you are there, it doesn't think, it only exists, and you think that it challenges you, that it defends itself, that it doesn't give up, when really it's you who starts the fight, no against the mountain but against yourself, seeking to overcome your fears and your weaknesses.

Meanwhile, Mauricio rappelled through the gutter to the place where he had been left, it was a length of rope of almost 40 meters; when he arrived he seemed concerned, he examined me cautiously and only then did we realize the true dimension of the problem. It was almost 5 in the afternoon, beaten on the Left shoulder almost without strength in that arm it was of no use to me, the glasses embedded in my face had hurt my eyelids and I had one EYE closed, the only place where I could bivouac was remained above, and without having an alternative we would have to continue hanging down the wall. Thus began the longest descent of my life, the most exasperating episode on the most beautiful mountain.

We signaled with the flashlight believing that they would understand the message: everyone calm down celebrating the victory. Seeing how slowly we were going down they figured we were in trouble, but they could only get as far as the base of the wall. Each rappel was an ordeal, installing them took forever; All the work was done by Mauricio and little by little he was running out; I tried to dissipate the anguish by remembering joyful episodes: the first time we saw it... “the South Face of the Canon”... it had to be ours, attempt after attempt it had become an obsession. 4 years looking for the way, 4 years dreaming of the summit, 4 years to reach the right moment; everything calculated, the perfect strategy, the support team, the artillery, two days examining each stone of the wall with binoculars, and the climb... the climb so natural that we couldn't feel the vertigo of the air steps , the climate conspired for success, we bivouacked in an atmosphere that transmitted that subtle warmth that must be felt when flying on a magic carpet; when we reached the summit it was incredible to us that we had achieved it. Everything had gone so well that what happened had to happen, and there we were playing the last cards, biting the bitterness of unforgivable mistakes when so much has been wandered through the mountains.

01:30 in the morning we arrived at the camp like two specters of the night. I couldn't sleep just thinking that it could have been...”the last climb”.

January 2, 1985, back at the Hospital where I worked, I would meet a person who changed my shape to take life.

Revista Montaña No. 16, 1989. Author: Fabián Cáceres

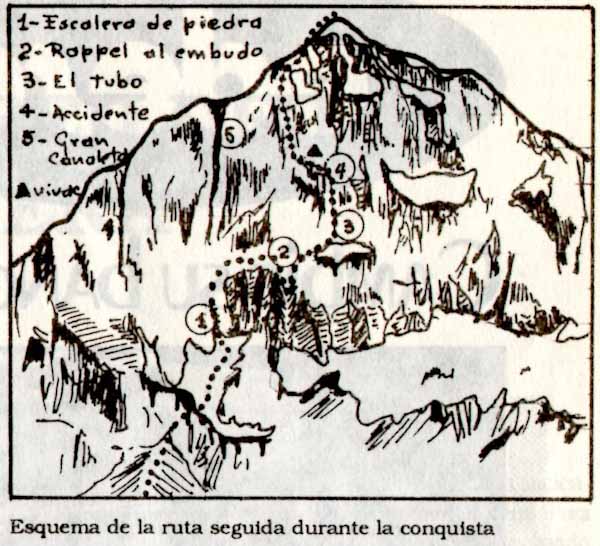

West Wall of the Tabernaculo, from the Altar cauldron

ON A WALL OF THE BOILER

After the usual hustle and bustle, preparations, farewells, etcetera, etcetera, I saw myself at last, fixing Al Amigo (trailer) On the road that goes from Penipe to Candelaria, I could not imagine that after so much time I could return to these adventures through the mountains of my country.

Taking advantage of the good weather and the skill of the mechanics that They repaired "the friend" so well, we were able to reach Candelaria at half past six in the afternoon, and without stopping we continued to the "Releche" hacienda, where we got the mules for the approach the next day as well as we were able to spend the night of comfortably, thanks to the kindness of the hacienda owner who gave us a room.

There were six of us adventurers who, leaving the year-end festivities, had decided to go to the mountains, Lucho Naranjo, Mauricio Reinoso, Carlos Cuvi, Peter Ayarza, Mauro Morán, and myself.

After spending the night at the hacienda, we left for Collanes, which was our next stop, making the most of the good weather prevailing that day, we advanced without complications to the blade, which leads to the north side of the Caldera, where we had, as usual, put on everything we needed. the mules had brought us from the hacienda, and it was only at five in the afternoon that we could reach the place where we made our first camp, with excellent weather.

Soon it got dark, and during dinner we all commented on how well that we were doing and the prospects for the following days, without even thinking how long the days that awaited us would be from now on.

During the night it started to rain and continued until the next day, and that above covered everything around us in white, and the intense activity that was seen the day before, carried out by several groups of climbers inside the "Caldera" disappeared completely, those of the North Face of the West were not bishop, nor those of the South Face of Canonigo, everything was postponed for another opportunity. We didn't have it, and with the vehemence that comes from that almost unconscious knowledge of things and the intense taste of adventure, we continued in good spirits.

We left at nine in the morning, and despite the drizzle, we continued until we found a pass where we could climb the upper ring of the "Cauldron" and approach the base of the wall of the Tabernaculo, which was our goal, we achieved it and during the day we were jumping crevasses, crossing bridges and ice ramps in the middle of a time that varied from hour to hour, and that by the end of the day cleared up, as a symbol a good omen.

The day ended at six in the afternoon, and we set up the second camp.

At night we had a unique panorama of its kind: surrounded to the north by the Canonigo and to the south by the Obispo, we could distinguish a large part of the valley that forms the province of Chimborazo, with its small towns and Riobamba, as if they were satellites or stars of a great constellation, and in the background the mountain that gives its name to this province, what an experience!!

At night they discussed the possible alternatives for the climbing the next day and although Lucho, Mauricio and Peter were sure of ascending the next day, I had not yet defined my situation within the group of climbers, perhaps to be able to sleep more peacefully that night, and not worry about the ascent that many posed. problems, although inside me I had already made a decision.

The next day looked good, because it dawned cloudy, which favored us for a better conservation of the snow and the glaciers, which hung over us, I informed them of my decision and we prepared to ascend: crampons, ropes, pegs, carabiners, straps, a sleeping bag, and something to eat was all our equipment, to try to get out of this wall.

We started climbing at 8 in the morning, and little by little we were overcoming different obstacles, until we reached a snowfield that was approximately a length of rope, we rested and took the opportunity to drink some liquid; and despite slowly climbing this wall, you feel with each step more the height that you are gaining. Little by little the panorama at our feet is changing; panorama that becomes more and more vertical and exposed.

I struggle to climb, he assures us, and we ascend like this a few times; and others Mauricio, until I decide to do a length of rope and I begin to feel how orphaned and defenseless a climber can be in the middle of this imposing wall due to the little security it offers; Well, it's a conglomerate of rocks, mud and snow that has no consistency, the rock crumbles when trying to put the pegs, or only places with dirt and snow are found that ends up turning into mud; others, on the other hand, are covered with "verglas" or too wet to be a good place; all this forces us to take extreme precautions when moving, without making mistakes. I finally finished this length of rope, after a short break, we continued the adventure, which became more and more exciting.

By four in the afternoon, and almost without rest, we reached a small blade on which we had to ride, and there being no other way out than to cross a canal that we had called “Spaghetti”; extremely exposed gutter, almost without dams and constantly swept away by avalanches of snow and ice that began on its upper wall, and which is a key step to be able to climb the wall. There was no other alternative than to try and Lucho did so , which meter by meter went deeper, slowly flanking its walls, making a great effort not to make any mistake that could plunge him into the abyss, he succeeded. For us, that step was the beginning of the end of the adventure on the wall, which was conquered with each step. From our small ledge on which we were riding, we could see the terminal glacier.

Soon we saw how Lucho and Mauricio, after leaving the canaleta, quickly reached the platform located between the Tabernaculo and the Monja Chica, thus culminating the effective climb.

For Peter and me, this was a stimulus that prompted us to continue with more enthusiasm, we saw how close we were to the end of the wall. We got down to business and while Peter retrieved material, I secured it. Suddenly I heard a noise on the right side of which we were ascending, I immediately saw how a huge ice sheet began to slide. As Peter poked his head out from behind a rock, I yanked with all my might on the rope, and then on Peter's backpack, and then all that pile of snow and ice passed like a train, which could have given us more. from a scare.

Little by little we recovered from the scare and with a quick step I left the wall, exhausted from the effort made but happy; Soon Peter also came out to confuse us all in a hug, and a prayer to the Creator that filled our eyes with tears.

Our surprise was greater when we saw that after such a formidable effort, resigned to spending the night in a bivouac, we were able to see a camp at the foot of the Monja Chica, which we later learned belonged to a group from the El Sadday Club, who gave us a lesson on good eating in the mountains, as well as a tent that saved us from dawn like four “crowbars” for the bad weather that broke out that night.

Today that I remember this, many pleasant memories and experiences remain floating in me that make me feel nostalgic for those moments, that make me see things differently, especially our strong group spirit.

Revista Campo Abierto No. 19, 1996.

Integral of summits, Altar Volcano, 1995

It was an Italian expedition, led by Marino Tremonti, which in 1964 reached one of the peaks of Altar, El Obispo, for the first time, and the following year, Tremonti himself climbed to the top of Canonigo and Fraile Grande. Although it's true that barely a month after the Italian conquest of the Obispo, an Ecuadorian group also reached that summit, the glory of being the first went to the foreign climbers.

Then the stage of the first from the other peaks of the massif, until 1978 when climbers from the Polytechnic Club reached the top of Fraile Beato, the only peak that had not been climbed until then in this beautiful mountain of our Andes.

In 1988, an Ecuadorian roped- French, achieves the first ascent to the Obispo from the caldera and a month later an Ecuadorian rope reaches, also from the caldera, the top of the Canonigo: these ascents have not been repeated until now.

When the Andean environment of the country, as we had stated in previous issues, was going through a stage of stagnation, pleasant news surprises us: a group of young Ascensionists from the Colegio San Gabriel, belonging to a new generation One of the country's mountaineers, performs a feat, unprecedented in Ecuadorian mountaineering, the conquest, in a single expedition, of all the important peaks of the Altar: Obispo, Monja Grande, Monja Chica, Tabernaculo, Fraile Beato, Eastern Fraile, Central Fraile, Great Fraile and Canonigo; This, although in real mountaineering terms it's a "chained conquest" of the nine peaks mentioned, given its novelty, the members of the expedition, and also us, have called it "the integral". The event took place between September 15 and October 5 of last year.

Although it was not possible to obtain a detailed account from any of the members of the expedition, from According to the general report and some conversations with them, the itinerary of the expedition was as follows:

FRIDAY 15

The group, made up of: Oswaldo Freire , Oswaldo Alcocer, Gabriel Llano, Edison Oña, Fernando Navarrete, Gaspar Navarrete and Eduardo Villaquirán, leaves Quito at 3:00 p.m. in two jeeps. At 8:00 p.m. the first of them arrives at the Sali intake, where they immediately proceed to hire muleteers and mules to carry the load up the mountain the next day.

SATURDAY 16

Pablo Fernández, who collaborated with the transport to this site, returns to Quito, while the rest of the group heads towards the mountain. At 2:30 p.m., the mules leave them on the ridge that leads to the Italian Camp, their goal for that day, at 5:30 p.m. they reach it. While five of the expeditionaries carry out a portage to a more advanced site, two of them proceed to set up camp. The group meets again at 8:30 p.m.

WEDNESDAY 17

At 11:00 a.m. they set off towards what would be Camp II, at the foot of the Obispo. They arrive at the site at 3:00 p.m. After setting up the tents, the whole group, with the exception of Gaspar, who would be in charge of the kitchen, proceed to carry out a portage, from which they return at 8:00 p.m. Camp II is at 4790 meters above sea level.

MONDAY 18

They set up Camp III, at the foot of Monja Grande and return to Camp II where they will spend the night, to try the ascent to the Obispo the next day.

TUESDAY 19

At 04:15, the Oswaldos, Gabriel and Edison, leave the camp and head towards their first target. Snow conditions are optimal. Following the route of the Italians, after four hours of climbing they reach the top of El Obispo, the highest in the mountain. The descent is fast and at 09:30 they are back at the camp. The support group, made up of G. and F. Navarrete and E. Villaquirán, returns to Guito, since one of its members is not feeling well.

The four climbers, who from now on will face the adventure, they dismantle Camp II and head to III, where they arrive after a three-hour walk on the glacier. Camp III is at 4940 meters above sea level.

WEDNESDAY 20

Bad weather forces climbers to stay in camp. At times, the tedium of staying inside a tent all day is greater than the satisfaction of resting.

THURSDAY 21

The weather doesn't has changed, forcing climbers to continue resting in their tents. In the afternoon the mountain clears and they immediately go out to explore the pass to the Tabernaculo. Three hours later, they return to camp.

FRIDAY 22

It dawns clear, so very early in the morning, at 04:45, they begin the ascent towards Monja Grande reaching the summit after three hours of climbing. The descent, as in El Obispo, is also fast and at 10:30 they are already on the march towards Camp IV

The mountain is once again covered in fog, reducing visibility to almost zero, which makes it difficult for the expedition members to always find the exact route. Only at 6:00 pm they set up Camp IV, at 4,890 meters above sea level, on the hill between the Monja Chica and the Tabernaculo.

SATURDAY 23

Bad weather. The group remains in their tents resting and organizing the equipment.

SUNDAY 24

The good weather has returned to the mountains, everything is clear. At 08:00 a.m. they head towards Monja Chica and at 08:50 a.m. they are already on its summit, the third so far in the expedition.

At 10:00 a.m., after a real breakfast , they head towards the unknown region of the mountain. The passage from the Tabernaculo to the Circus of the Friars, no one has made this journey before, so there is a great unknown in this regard. After going through countless cracks and ridges, they find the ideal place to set up Camp V, at the base of the eastern face of Fraile Beato. At 2:30 p.m. they are back at Camp IV. Edison, who hasn't had a good night, isn't feeling well

MONDAY 25

A big snow and wind storm hits the mountain. Day of forced stay inside the stores.

TUESDAY 26

The day dawns cloudy, however at 09:40, Gabriel and the two Oswaldos head to the Tabernaculo; at 11:50 a.m. they reach the summit in the midst of the fog and wind that blow through the mountain and at 12:30 p.m. they are back at the camp.

At 2:00 p.m. they leave in pursuit of Camp V, which they arrive at 5:00 p.m. They are located at 4,960 meters above sea level.

WEDNESDAY 27

Bad weather forces climbers to stay near the camp. Whenever it's possible, they look for a passage through the Fraile Beato ridge to access the Cirque de los Frailes. The Cirque of the Frailes, is named for the semicircular shape of the glacier enclosed between the four peaks called Frailes: Beato, Oriental, Central and Grande and the edge that descends from the summit of the Grande and separates the circus, del Canónigo.

THURSDAY 28

At 06:00 they set off towards the summit of Beato following its eastern edge, but they soon realize that this is not the indicated route, since large ice gendarmes block the passage at all times. They return to the camp and after setting it up, they head towards the cirque formed by Los Frailes, in search of a new place to camp that offers better access to these summits.