Revista Montaña No. 16, Evelio Echevarría

In a book written during the Colony, the mayor of Quito, Toribio de Ortiguera, describes the eruption of that year of the "frightful volcano and mouth of fire that is near the city of Quito". Follow the parts about the arrival to the top and crater of 4,791 meters:

... Eager to see by sight of eyes such a strange thing and where the cause of it came from, the graduate Francisco de Auncíbar determined ... to see him personally. He asked with determination to say Mass there, Don Alonso de Aguilar, priest of the holy cathedral church of Quito, and Juan Sánchez Miño ... to Captain Juan de Galarza ... to Captain Juan de Londoño and Toribio de Ortiguera, who is the one who writes this relationship, besides which were many other Spaniards and Indians and Indians, blacks, blacks of service. We left Quito Saturday after noon, July twenty-eighth of the 82nd ... the next day Sunday ... we climbed the hill on foot because it was very rough and with terrible rocks, all covered in ash, snow and ice, with air so cold that it blinded us with ash and very cold... Arrived we went to the mouth of the volcano or mouth of fire, because there was no thing that prevented it, we saw it, and it's in this way: that it's in a hill, the highest and scarred of all there is in all that circuit, in the middle of which is the spacious hole in which there will apparently be more than five hundred states of depth and in the beginning and round the mouth will have a league of a circle. .. This mouth has a strange annoyance: that with having in the depths and depths of her fire and the fumes that have been seen, at the beginning and high of her it's so terrible cold and in such a way that none of the priests were able to say mass ...

Nevados de Ecuador y Quito Colonial, Ángel N. Bedoya Maruri, 1976

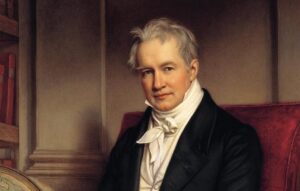

Alexander von Humboldt, by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1781 - 1858, German painter

I managed to arrive on May 26 and 28 of 1802 on the edge of the Pichincha crater, a mountain that dominates the city of Quito. So far no one, who knows, if it's not La Condamine had never seen it and Condamine himself had not reached it but after five or six days of useless travel and without instruments and could not stay there more than twelve or fifteen minutes because of the cold I was doing. I managed to bring my instruments there; I took the measurements that were interesting to know, and I collected air to do my analyzes. I made my first trip only with an Indian. As the Condamine had approached the crater by the lower part of its snow-covered edge, it was there where following its tracks, I made my first attempt.

But we escaped from perishing, the Indian fell to his chest in a crack and we saw with horror that we had walked on a bridge of frozen snow; then, a few steps from us there were holes through which the light passed. We were then, unknowingly, on top of vaults that are attached to the crater itself. Scared, but not demoralized, I changed my project. From the contour of the crater come out, launching, so to speak, three peaks, three rocks that aren't covered with snow, because the vapors exhaled by the mouth of the volcano melt them incessantly. I climbed to one of those rocks and I found in its summit a stone that being supported on one side only and undermined underneath, advanced in the form of balcony on the precipice, There I settled down to make my experiences. But this stone is no more than about twelve feet long, six feet wide and is very shaken by frequent tremors, of which we count eighteen in less than thirty minutes. To better examine the crater bottom, we lie face down and I don't think the imagination can be something more sad, dismal and frightening than what we saw then. The mouth of the volcano forms a circular hole of about a league of circumference whose edges, cut to peak, are covered with snow at the top; the interior is of a dark black, but the abyss is so immense, that the top of several mountains that are placed in it's distinguished, its summit seemed to be three hundred toises below us; I judged then where its base should be. I don't doubt that the bottom of the crater is at the same height as the city of Quito.

Carta dirigida al profesor Guillermo Jameson, 1857

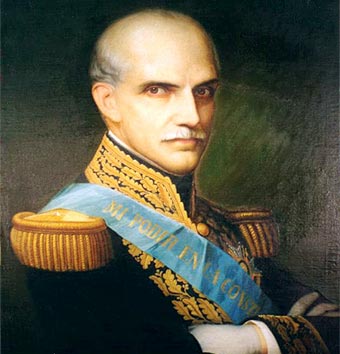

Gabriel García Moreno, President of Ecuador, 1861-1865 and 1869-1875

Dr. Gabriel García Moreno, President of Ecuador, was in addition to being a politician, a scientist and an athlete. Its historians refer that García Moreno ascended the Pichincha volcano five times and descended to its fumaroles. it's also said that he once visited the Sangay in full eruption.

Below we offer the account of García Moreno himself, made in December 1857, according to a letter addressed to his friend, Professor Guillermo Jameson.

My dear friend:

Here is a brief review of my last trip to the volcano that dominates Quito. The short distance to which the Pichincha volcano is located from this city has contributed to excite the curiosity of scientific travelers who have visited the territory of Ecuador, also causing the state and shape of said volcano to be well known.

Bouguer and La Condamine were the first to reach the crater in 1742. The famous Alexander of Humbolt in May 1802 ascended twice over the gigantic wall of dolerite that forms the eastern edge of the volcano; and some thirty years later the ill-fated Colonel Hall, your countryman, and Mr. Boussingault followed the same path, but since 1844 when Mr. Sebastian Wisse and I went down to explore it, no one has gotten to the bottom. In August 1845 we returned with the intention of raising the topographic plan of the volcano, measuring the heights, etc., and in order to carry out this purpose, we had to spend three days and three nights in the two deepest cavities that form the volcano.

DESCRIPTION OF THE CRATER

In an orographic view, our second expedition gave us the results we longed for. The Pichincha, located to the south west of Quito, forms two large cavities, one to the east of the eastern cavity called the eastern crater without sufficient reason, it has the shape of a narrow, long and deep valley, through which one runs from north to south a stream that receives the rains and melted snow.

At the top of this basin there is a slight depression of elliptical shape and perfectly horizontal at the bottom, very similar to a small lake in the Alps, dried by the sun, depression that at the same time suggests by its shape the existence of some extinct crater. The depth of this supposed crater is 320m. under the eastern wall, and since the highest of it reaches 4798 m. Above sea level, the altitude of the bottom of the eastern crater is 532 m.

The western cavity or more deeply the true crater of Pichincha, is one of the most important objects that can occur to the naturalist. Located on the western slope of the Pichincha, and different from the other craters of Ecuador, which are found on the cusp of regular cones covered with snow, this one has the figure of a truncated cone, placed on its base lower (lower?), which is 450 m. in diameter and rises to a height of 700 m.

Its depth from the eastern edge is enormous, and when one looks over the immense towers of dolerite and trachyte whose elevation is 750 m. sometimes cut vertically and on more or less steep and varied slopes, one experiences such an impression that it doesn't fade throughout his life. Towards the western part the height of the crater walls gradually decreases, leaving the west open a crevice through which rainwater and thaw escape together.

THE ERUPTION CONE

In the middle of the inclined plane that constitutes the bottom of the volcano, the current cone of eruption rises; it's 250 m. diameter, 80 m. high above the bottom of the middle of the crater and 4177 m. above sea level, being 1269 above Quito. This little hill is the center of the Pichincha activity, and in 1845 it offered clear indications of remaining in that state for many years, with no increase in intensity. Much of this cone is covered with vegetation. Two ravines, departing in different directions, surround him completely, until they join in the cleft of which I have spoken; and at the two points from where the eruption cone depresses (one in the center and the other to the SE), a hot and sulphurous vapor is released in abundance, coating the voids and interstices of the rocks from which it's formed with sulfur. it makes up the cone.

During the 1845 expedition, it was not possible for us to study the volcanic and plant products that the crater presented. To examine his current state and make up for this lack, I descended on December 16, carrying as much as possible what was necessary for the dangerous situation in which I expected to be placed. I was busy for a little over three hours on the descent, and at eleven thirty in the day I found the side of the eruption cone. The form it presents shows that the bottom of the Pichincha has recently been the scene of considerable convulsions. The vegetation that covered it has disappeared on the eastern side; the depression that exists towards the SE, at the foot of the cone has widened, and has filled a part of the cut enclosure, obstructing perpendicularly a wide wall of stones undoubtedly thrown from the interior.

Near it and towards the South, since 1845, a new depression or, more properly speaking, a new western crater has formed from which a great mass of steam rises, so that the eruption cone currently has three openings or craters: the main one, which occupies the highest part; the old western crater, located to the SE, and the new open western crater, apparently at the foot and south of the main one.

THE VAPORS

The Pichincha's volcanic activity has increased notably, as manifested by the increased exhalation of vapors. In 1845, the chimneys through which the gases exited, formed six groups of which only one was considerable. Now the vapors escape through innumerable interstices and holes, which leave the stones in each of the craters, and in the main one a noise similar to that made by an immense cauldron of boiling water is heard.

Filling with water a graduated tube, and placing it inside the interstices, I collected the gases several times, in order to analyze them, and also condensed them by means of a bottle of cold water and collected the drops of the liquid that formed. The result of me is that the Pichincha gases contain traces, barely perceptible, of sulfurous, sulfuric and hydrogen sulfide acid, four percent carbonic acid and the rest composed exclusively of water.

HOPE TO RETURN

I left Pichincha on December 18, after having spent the previous night inside the crater at 150 m. of the eruption cone. Eager to continue my observations, I hope to return to the crater this year, in order to spend a few days inside, and I will regard my last expedition as a preparatory and necessary step for a more important one.

Before If I undertake it, I will find the point where the descent to the bottom of Pichincha can be easier, avoiding the eminent danger of falling down the eastern wall.

In 1844 Mr. Wisse was fortunately saved, about to roll headfirst into a hideous abyss. The same accident happened to me in 1845, and in December of last year, your son who accompanied me almost found his grave in the abyss. I don't doubt that when descending 740 m. made of rocks where the hands serve more than the feet, a reckless step would have very fatal consequences.

I am yours, a very attentive and secure servant.

Gabriel García Moreno

Nevados de Ecuador y Quito Colonial, Ángel N. Bedoya Maruri, 1976

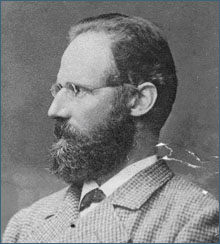

Wilhelm Reiss (13 June 1838 – 29 September 1908), German geologist and explorer

The 19th before sunrise we had reached the edge of the crater, if in general, we can speak of a ridge or edge of a crater, because the whole hill is excavated, opening to the west and northwest frightful and abrupt rocks that surround the great caldera, whose interior is decomposed by some backs in a series of valleys. The northern part of this large caldera is separated from the rest by a high wall of rocks, whose interior falls almost perpendicularly form a small caldera or crater. At its bottom, that is to say, at the bottom of the boiler, there is a number of quite active fumaroles, whose gases, meeting in a single column, emerge as white clouds on the ring road. it's a caldera like in the volcano of Pasto, in Chiles and in Cerro Negro, valley-caldera that can be compared to that of Palma, but it can never be characterized as a crater. The fast walls (at its top can be calculated in 400 to 500 m depth) that surround it, are covered with new ice and prevented any attempt to get inside. The view from the different parts of the edges of the boiler is wonderful; on the one hand the deep caldera, with walls of black rock, the white clouds formed by the gases and that go towards the west, towards Esmeraldas and that forms the Mindo river; on the other hand, the few scattered descents of the conical mountain, covered with ashes and fragments of pumice stone, of which immense masses of black lava stand out, forming the highest peak; below, the pajonales and the narrow zone of the forest that limits in its upper part to the wide prairie valley of Lloa.

Travels amongst the Great Andes of the Equator, Edward Whymper

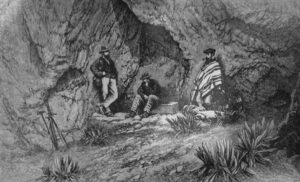

The second camp on the Pichincha.

The second camp on the Pichincha.Before proceeding to the north, we made an excursion to the top of Pichincha. So far as extent is concerned, this is an important mountain. The part of it that is 10,000 or more feet above the level of the sea is quite fifteen miles from North to South, and its summit rises 6000 feet above Quito. Yet there is little about it of a thoroughly mountainous character. it's composed principally of undulating, grassy slopes, over which one can ride higher than 14,000 feet. it's impossible to feel great respect for an eminence that can be climbed on donkey-back, and the truth is that the ascent of Pichincha is scarcely more arduous than that of the Eggischorn.

We left Quito on the 21st of March, at 7.55 a.m., with a team of seven animals and three arrieros; passed to the west of the Panecillo (by the road shewn on the Plan) through the village of Magdalena, and (leaving Chillogallo on the left) commenced to mount the slopes of Pichincha; going at first over a small col, and descending on the village of Lloa, then ascending through meadows, followed by a considerable stretch of wood. In an unctuous rut between walls of earth, one of our mules floundered and fell with its legs doubled underneath; and our chief arriero —a Chillogallo man—after a few feeble efforts, would have abandoned it on the spot. Then we experienced the usual afternoon shower-bath, and, getting into the clouds, became perplexed as to our whereabouts. Camped at 4 p.m. in sleet and drizzle, unable to see a hundred yards in any direction, and sent the animals and natives back to Lloa. At night, when the atmosphere cleared, it was seen that we had camped about midway between the two peaks of Pichincha, which we conjectured were those that are called Guagua and Rucu.

Although there are numerous allusions in the works of previous writers to these summits and to the craters of Pichincha, and we had met various persons in Quito who claimed to have visited the eraters (for it was said there were several), I was unable to tell from anything that had been said or heard what was the relative position of the summits, or where the craters were located; and when these two peaks made their appearance we were not certain which of the two was the higher. The right hand or eastern one appeared to be the lower and the easier to ascend, and I sent Louis to tackle it, while Jean-Antoine and Verity went to pay their attentions to the other.

During their absence I mounted to the depression in the ridge connecting the two peaks, or ensillada as it's termed, and found that on the other side it descended very steeply. So far as mist would permit one to see, this was the head of an ordinary mountain valley. I awaited the return of my people, and, as their reports agreed that the western peak was the higher, shifted our camp in the afternoon up to a sort of cave that had been discovered by Jean-Antoine, a convenient place (where some cavities in the lava were protected by overhanging masses) roomy enough to let each one select a nook for himself; and my assistants, consetpaently, were able to snore ad libitum, without having their ribs poked with an ice-axe.

From this refuge, which was just a thousand feet below the top of Guagua-Pichincha, there was an extensive prospect to the south and east. We saw the summits of Illiniza and Corazon rising immediately over that of Ataeatzo; and Cotopaxi and Antisana (each nearly forty miles away) by moonlight. In the night I heard, at irregular intervals, roars (occurring apparently at no great distance) exactly corresponding to the noise made by the escapes of steam from the crater of Cotopaxi. The minimum temperature at night was 29° Faht.

On the next morning (March 23) all four of us followed JeanAntoine's track, and upon striking the western ridge of Guagua I found there was a very precipitous fall on the other (or northern) side, where the crater, presumably, was located. We crossed this ridge, and after descending about four hundred feet saw that we were in the valley that I had looked down upon from the ensillada. While the upper part of it was rocky, precipitous, and bare, the slopes below were covered with a good deal of vegetation; amongst which there was neither smoke, steam, fissures, nor anything that one would expect to see at the bottom of the crater of a volcano which is said to have been recently in eruption. This however, no doubt, is a crater of Pichincha. Its depth, reckoning from the highest point of the mountain, is probably not less than two thousand feet; its breadth is fully as much, and the length of the part we saw was at least a mile. It had none of the symmetry of the crater of Cotopaxi. The western extremity was clouded during the whole of our stay on the summit.

We then reascended to the arete of the ridge, and followed it until Jean-Antoine said that the top was reached. The rocks fell away in front, and there was no reason to doubt him; but, while the barometer was being unpacked, some crags, a long way above, loomed through the mist. "Carrel," I said, "if we are on the summit of Pichincha, what is that?" He was spickup truck dumb for a time, and gasped "Why, I never saw that before!" We shut up the barometer, and went on, and in half an hour were really on the top of Pichincha. Nothing more need be said about the ascent than that it might be made alone, by any moderately active lad. The right way up the final peak is by the ridge leading to the west, and it's probable that this route has been taken before, for on the other sides, although not inaccessible, the last eight hundred feet are very steep. I found that the summit of Guagua-Pichincha was a ridge of separated by a wall of rock.

I found that the summit of Guagua-Pichincha was a ridge of lava about one hundred and fifty paces long, mainly firm rock, though strewn with loose, decomposing blocks, amongst which there were a number of lumps of pumice, up to a foot or rather more in diameter. Close to the very highest point (15,918 feet) a little pile of stones had evidently been put together by the hand of man. Snow-beds were somewhat numerous in fissures, yet the top of this mountain scarcely touches the snow-line.

The whole of the summit-ridge had an appearance of age, and bore a large quantity of lichens (Gyrophora sp., Lecidea sp., and Neuropogon melaxanthus, Nyl.); and within fifty feet of the extreme top there was a large plant, with thick, woolly leaves, and a nearly white, pendent, downy flower—I presume, a Culeitium—which was one of those that constantly attracted attention by recurrence at particular altitudes. It made its appearance whenever we reached the height of 14,000 feet, and was never seen much lower. From its size and prominent characters it was not readily overlooked, and I cannot be far wrong in estimating that its range in altitude extends from about 13,500 to 16,000 feet above the level of the sea.

Twenty-one species of Beetles were collected upon Pichincha between the heights of 12,000-15,600 feet, belonging principally to the Carabidcc, Otiorrhynchidee, and Cureulionida: The whole are new to science...

Geografía y Geología del Ecuador, Teodoro Wolf, 1892

Theodor Wolf, 1841 - 1924, German Scientist

El Pichincha is the first volcano of historical activity, and at the same time the only one in the Western Cordillera. Today he is asleep, but not completely turned off, and not many years ago he gave signs of waking up again. it's probable that, at the time of the conquest, he was in a similar state of tranquility. For the first time it frightened the inhabitants of Quito 32 years after the foundation of this city, with a strong eruption, on October 17 and 18, 1566, and on November 16 of the same year. September 8, 1575 the same event was repeated with more force, and again on June 14 and from July 11 to 14, 1582. After a vigorous activity of 16 years, the Pichincha calmed down and did not bother to the people of Quito for 78 years. But then, on October 27, 1660, he woke up suddenly and made the most frightening eruption that History remembers. There are many authentic documents in Quito about this event. it's one of the largest volcanic phenomena presented by the History of Ecuador; and as if the Pichincha had exhausted all his strength with this eruption, he fell back into a deep lethargy, without rising from then on to a somewhat considerable activity.

The crater is in the state of solfatara, exhaling aqueous vapors and sulphurous gases: sometimes a column of smoked smoke rises over the top of the volcano, and it's probable that also in our century (XIX century) it made some weak eruptions, that went almost unnoticed in the Capital, for example, towards the year 1830, and March 10, 1881.

From the old relationships we can deduce that the eruptions of crushed materials are composed of ash, sand, lapilli, pumice, bombs of all kinds and fragments of lava and andesite. Currents of fresh lava (historic) we don't know in this volcano, at least not on its eastern and southern sides. If there are some, they should be looked for in almost inaccessible western skirts, towards where the crater is open.