Nevados de Ecuador y Quito Colonial, Ángel N. Bedoya Maruri, 1976

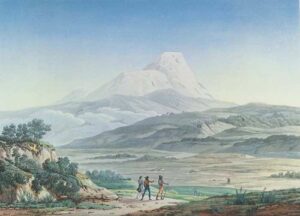

The “Cayambe Volcano” (Vues des Cordillères et monumens des peuples indigènes de l"Amérique, lámina XLII)

The Cayambé (with acute accent in the vowel e) is the highest peak of the mountain ranges, after the Chimborazo, and its height has been calculated with some precision, Bouguer and La Condamine assign it 5,901 m. determination confirmed by measurements that I have taken in the Ejido of Quito, to observe the march of the terrestrial refractions at different times of the day. French academics call this colossal mountain Cayambur instead Cayambé Urcu which is its real name. The urcu voice means mountain in Quechua, like tepetl in Mexican and gua in Muisca. This error is found in most of the works that present the picture of the main heights of the globe.

The Cayambé has the shape of a truncated cone, reminiscent of Tolima"s snow-capped mountain and is the most beautiful and majestic peak covered with perpetual snow, of those around the city of Quito. When, At sunset, the volcano of Guagua Pichincha, located west towards the South Sea, casts its shadow over the vast plain that forms the foreground of the landscape, the show is worthy of admiration for its charm. The plain, upholstered with grasses, has no trees; only some barnadesia, duranta, beriberis and beautiful calceolarias are seen, which almost exclusively belong to the southern hemisphere and western region of America.

Distinguished artists from the north have unveiled the Kiro River waterfall near the village of Yervenkyle in Lapland, where the polar circle passes according to observations of Maupertuis and Swambberg. Ecuador crosses the Cayambe summit: it can be considered as one of those eternal monuments through which nature has signaled the great divisions of the terrestrial globe.

Travels amongst the Great Andes of the Equator, Edward Whymper

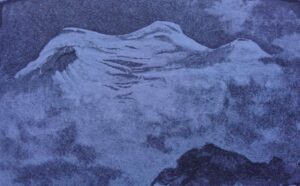

Edward Whymper drawing, Cayambe from the west

Cayambe culminates in three domes or bosses, all completely enveloped by snow-covered glacier. The only visible rock high up on the western side is a small cliff, about 800 feet below the northern of these three summits, which is capped by a vertical section of ice, similar to that shewn in the plate facing p. 76. From examination of this mountain at great distances, it was known that the central boss was the highest. It bore north-east from the Pointe Jarrin, and appeared to be more or less accessible, though decorated at its crest with overhanging cornices and surrounded by large crevasses. The course agreed upon was 20° East of North for the first part of the way over the lower glacier; with the intention of bearing round to the south, and steering directly for the summit, after having got clear of the fissures at the head of the ice-fall. To save time on the following day, I caused steps to be cut up the rounded slopes of the glacier where they pressed against the Pointe Jarrin, and in the course of the afternoon advanced food and instruments to the edge of the ice.

On the 4th of April we left the tent at 4.40 a.m., and walked by lantern-light as far as the top of the Pointe Jarrin. The morning was fine and clear, and the view at this time embraced almost all of the mountains which have hitherto been enumerated. After traversing some flat and easy glacier, we became involved in a complicated maze of snow-covered crevasses at the head of the ice-fall of the Espinosa Glacier (Glaciar Hermoso), which had to be threaded cautiously. This was followed by moderatelyinclined slopes, and we then entered upon a large plain that took three-quarters of an hour of steady going to cross. This we called the Grand Plateau. Afterwards the slopes became steeper, with occasional large open crevasses and numerous concealed ones, and were rapid near the top, which was gained soon after 10 o"clock in the morning.

Early in the day mists began to form and gather beneath us, and we pushed on to endeavour to have a view from the summit. At 9.30 a.m., when quite a short distance below the highest point, we were well seen by a crowd assembled on the Plaza of the village; but in a few minutes more the clouds caught us up, and we did not get out of them until the close of the day.

The true summit of Cayambe is a ridge, running north and south, entirely covered by glacier. Its height (deduced from the mean of two readings of the mercurial barometer at 10.45 and 11 a.m.) is 19,186 feet, and this mountain is therefore the fourth in rank of the Great Andes of the Equator.1 Of the other two summits the northern one is the higher, and it's well-nigh inaccessible, being almost surrounded by gigantic crevasses, and surmounted by tufted cornices. The central or true summit presented fewer difficulties, though it was not altogether easy of access. It was a stroke of good fortune to find a snow-bridge across the highest crevasse, just under the place where there was a break in the coronal cornice.

Glacier departs in all directions from the summit of Cayambe in a manner that is seldom seen on mountain-tops. From the huge schrunds that surrounded the three bosses of the summit-ridge, on all sides, I think that there are at no great depth beneath the surface several pinnacles like those which form the summits of Sincholagua and Illiniza. By persons who are familiar with glacier-clad eminences it will be apprehended without saying that a slight diminution in the thickness of the superincumbent ice may cause the apex of this mountain to become inaccessible.

During the 83 minutes we remained on the summit, temperature fluctuated between 32° - 41° Faht. On arrival, the wind was light, without any very pronounced direction. It strengthened as day advanced, and soon after 11 a.m. blew in squalls from the east, and we retired. The upper part of this mountain was a regular battlefield for the winds. On several occasions in the succeeding fortnight, when encamped southwards, we saw their struggles for victory. If the east wind conquered, the whole mountain became invisible; but if, as happened some times, a north-west wind prevailed, then the western side, and even the rest, was seen.

It being still early in the day, we diverged to the north to get some samples of the highest rocks;- and then followed our track literally, as the mists were dense,—proceeding very cautiously, "sounding" at almost every step in consequence of the increased softness of the snow, and grovelling on hands and knees across the rotten bridges. We returned to camp at 3.40 p.m.