Grandes Naturalistas en América, V. Wolfgang von Hagen

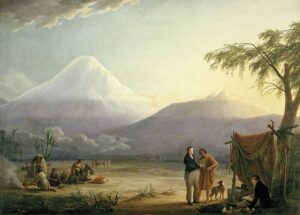

Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland at the foot of Chimborazo Volcano. Autor: Friedrich Georg Weitsch (1758–1828)

In the youth of Humboldt, the Chimborazo had the fame that gave him a sort of celestial legend to be the highest mountain in the world. In the secret chemistry of emotions, man is drawn incessantly by all that it's less accessible. Thus, it was inevitable that Alexander von Humboldt would attempt the ascent to Chimborazo.

Wherever Humboldt and Bompland went in the Audiencia of Quito, they saw the frigid mass of the Chimborazo, covered with snow, calling to them, making them acquainted. Nobody had ever climbed to the top. For the Indians it was inviolable, for the criollos inaccessible. Actually, the first part of his eight months of stay in Quito, was only a preparation for the assault on Chimborazo.

The contact with Humboldt and Bompland galvanized the feelings of Carlos Montúfar. Before these modern Europeans he realized how deep the isolation of the new world kingdoms had been. He was destined to go with Humboldt everywhere - to Chimborazo, to the Amazon, to Lima, to Mexico, Paris, and London, and all these trips were but preparations for the second American revolution. But, as often happens with young people, Carlos Montufar anticipated. In 1810, after three months of delirious revolutionary government, he was shot in the Plaza de Quito. But, in June 1803, he was preparing, with Humboldt and Bompland, for the ascent to the great Chimborazo volcano.

They left Quito on June 9 riding through the long inter-Andean valley ; They passed through the cities of Latacunga and Ambato, hung in the sky, by the dry and desert wasteland located at the base of Chimborazo. On the night of June 22, they slept in the small hut of the mayor of the village of Calpi. At dawn the next day, with Indian guides, they began their historic ascension. The first 1,803 meters were gradual and easy, but then the road became steeper and steeper. When they reached the snow line, their Indians, deaf to promises and even to threats, abandoned them and descended the slope, and left the expedition without porters and before 2,000 meters to climb yet.

Little by little they were ascending through the frozen fissures of the mighty Chimborazo.

We moved on, Humboldt recalled later, more slowly, since all the places that seemed unsafe had to be tested first ... Fortunately, the attempt to reach the top of the Chimborazo had been reserved for our last big company ...

At 5,185 meters they could not see the top. Now there were other difficulties. One after another, according to the metabolism of each one, the explorers began to feel nauseous and vertigo. Their lips and gums bled. Some windows in his eyes broke and the blood partially blinded them. Carlos Montúfar bled profusely from his ears and mouth, but refused to give up. A few hundred meters above, they saw again the domed cusp.

"It was a magnificent and solemn show, and the hope of reaching the goal of all our efforts gave us new strength." Then, precisely when they thought they could reach the top, they reached a deep abyss, so wide that there was no possibility of saving it. The Chimborazo had successfully challenged all efforts, including Humboldt's. It was in the afternoon. The temperature was below one hundred degrees. Don Carlos was visibly ill. They took out their barometers and saw, for the last time, that the mercury marked 2/1110 inches, which showed, according to the barometric formula of the day, that they had reached a height of 19,186 feet (5,872 meters). This was the highest height that man had ever reached , and it was not surpassed until the climber Webb climbed the Himalayas.

All my life I had thought, Humboldt wrote, already old, that of all the men I was the one who had climbed the highest in the whole world.

Towards the end of his life, at an age when men don't speak lightly, he said that he still considered Chimborazo as the greatest mountain in the world. And when in 1859 he posed for his last portrait, venerable titan with his hair as white as the glaciers of Chimborazo, the figure bent by age, his face as serene as Zeus's, insisted that he be painted without any of his decorations. Instead, he suggested that the great mountain of Chimborazo be placed as a backdrop; Of all the exploits he had done in his ninety years of life, he considered this as 'the greatest'. Humboldt stopped only the time necessary to put in his pocket some pieces of Chimborazo rock, because he foresaw -this man so human- that 'in Europe they would ask us for a fragment of the Chimborazo'.

My Delirium on the Chimborazo

My delirium over the Chimborazo. Painting of Tito Salas in the Casa Natal & Museo Bolivar, Caracas, 1929.

I was wrapped in a cloak of the Iris, from where the tributary Orinoco pays tribute to the god of waters. I had visited the enchanted Amazonian fountains, and I wanted to go up to the watchtower of the universe. I looked for the footprints of Condamine and Humboldt; Follow them boldly, nothing stopped me; reach the glacial region; the ether suffocated my breath. No human plant had trampled the diamond crown that placed the hands of eternity on the lofty temples of the dominator of the Andes. I said to myself: this mantle of the Iris that has served me as a standard has traveled in my hands infernal regions, crossed the rivers and the seas and climbed on the shoulders of the Andes; the earth has been leveled at the feet of Colombia, and time has not been able to stop the mark of freedom. Belona has been humiliated by the radiance of the Iris, and can not I climb over the gray hair of the giant of the earth?

Yes, I will can! and snatched away by the violence of a spirit unknown to me that seemed divine to me, I left behind the traces of Humboldt clouded the eternal crystals that circulate the Chimborazo.

He arrived as if driven by the genius who animated me, and I fainted when I touched the crown of the sky with my head; I had at my feet the threshold of the abyss.

A feverish delirium filled my mind; I feel like I am ignited by a strange and superior fire, it was the God of Colombia who possessed me. Suddenly, time presents itself. Under the venerable face of an old man laden with the spoils of the ages; frowning, leaning, bald, curling his complexion, a sickle in his hand ...

"I am the father of the ages, I am the arcane of fame and secret, my mother was eternity, the limits of my empire are marked by the infinite, there is no grave for me, because I am more powerful than death; the past, I look at the future, and through my hand passes the present. Why do you bloat little child or old man or hero? Do you think your universe is something? That to rise above an atom of creation is to elevate yourself? Do you think that the instants you call centuries can serve as a measure for my arcana? Do you imagine that you have seen the holy truth? Do you foolishly suppose that your actions have any price in my eyes? Everything is less than a point to the presence of Infinite who is my brother. "

Overwhelmed with a sacred terror, "How, O Time!" I replied, "must not vanish the miserable mortal who has risen so high? I have passed all men in fortune because I have risen above the head of all the earth with my plants, I reach the Eternal with my hands, I feel the infernal pressures boil under my steps, I am looking at me shining stars, the infinite suns, I measure without astonishment the space that contains matter, and in your face I read the history of the past and the thoughts of destiny ".

"Observe, I tell myself: learn, keep in your mind what you have seen, draw in the eyes of others the picture of the physical universe, of the moral universe, don't hide the secrets that heaven has revealed to you, tell the truth to the men".

The ghost disappeared.

Absorbed, stiff, to put it that way, I was left for a long time, stretched out on that immense diamond that served me as a bed. In short, the tremendous voice of Colombia shouts at me; I rise, I sit up, I open my heavy eyelids with my own hands: I am a man again and I write my delirium.

Viajes Científicos a los Andes Ecuatorianos, M. Boussingault, 1849

Jean Baptiste Boussingault, french chemist (February 02, 1802 – May 12, 1887).

My observations about the traquitas of the Cordilleras could not be finished better than by a special study of the Chimborazo. For this it would have been really enough to approach the base, but what decided me to pass the limit of permanent snow, in a word, what determined my ascension was the hope of obtaining the average temperature of a station extremely elevated , and although this hope was frustrated, not for this reason I believe that my excursion has been entirely useless for science. I thus state the reasons that led me to the Chimborazo, because I reject dangerous excursions to the mountains when they aren't undertaken in the interest of the sciences ... My friend Colonel Hall, who had accompanied me already Cotopaxi and Antisana, wanted to do so in this expedition, eager to increase in it the data that was collected in respect to the topography of the province of Quito, and continue their research on the geography of plants.

The next day, at 7 in the morning, we went to the Arenal . The weather was clear and serene. To the east we discovered the famous Sangay volcano in the province of Macas, which La Condamine had seen a century ago in a constant state of incandescence...

We continue, and, without dismounting, we cross the limit of the permanent snow, and only at the height of 4945 meters where the terrain is already entirely impracticable for the mules we leave them with the certainty that few have ridden on horseback. similar heights , because this requires many years of practice in the Andes. These poor mules had already tried many times to make us understand their fatigue by completely dropping their ears and looking again and again towards the plain at every step, because these animals have a truly extraordinary instinct. After having recognized the point in which we were, we noticed that to reach an eminence that was heading towards the summit of the Chimborazo it was necessary to climb before a scarp slope that we had in sight and that was composed of stones of all sizes covered more or less with ice, and in parts it was seen that these pieces of rock rested on the hardened snow , and that consequently they would have recently detached from the top of the mountain. These landslides are frequent, in the midst of the snowcapped mountains, and the most fearsome are those that drag more stones than snow...

Finally, we arrived at the eminence in the form of edge that we proposed to follow until the summit. Unfortunately it was not as comfortable as we thought it from afar, little snow covered it's true; but in compensation it had slopes so steep that it was not easy to climb them without making unprecedented efforts, and in these aerial regions the gymnastic exercises are quite painful. Finally we come to a vertical wall, cut in trachitic rock, many hundreds of meters high. Here we felt a visible moment of discouragement, the barometer indicated that we were only 5680 meters above sea level, lower than the height we reached in Cotopaxi, and also the height of the last station of M. de Humboldt on the Chimborazo, where at least we wanted to arrive. When the mountain explorers begin to feel discouraged, the first thing they do is sit down, and we did it in the station of Peña Colorada. It was the first time that we allowed ourselves to rest sitting down: and as thirst devoured us, our first occupation was to suck ice to placate it...

Then Colonel Hall and the Negro went around the rock I was on, and they prepared to meet me, since I had to slide on the ice about 25 feet to join them, an operation that was executed without accident, but a stone, falling from the top, hit Colonel Hall and made him fall. I thought he was hurt, until I saw him get up and examine with his lens the mineral sample that he came so brutally to submit to our investigations: it was a piece of trachyte rock, identical to the rock where we climbed...

The snow began to hinder and make our march dangerous, because there were only three or four inches of soft snow on the hard and slippery ice that was below and that it was necessary to sting to confirm our steps. This work was done by the black, who was ahead, but as he tired so much, I wanted to move forward to relieve him, when I slipped suddenly, although fortunately Colonel Hall and the black man held me back, running all three at that moment the most imminent risk. This circumstance made us hesitate, but taking a new resolution we continued, and the snow being firmer, we made the last efforts to climb the angle of rocks we wanted, which we finally reached the one and three quarters. There we were convinced that it was impossible to pass forward , we were at the foot of a trachyte prism, whose upper base, covered with a snow dome, forms the summit of the Chimborazo.

The place where we had climbed was a small parapet a few feet wide, surrounded on all sides by precipices, and in whose contours nature presented the most capricious accidents. The dark color of the rock contrasted with the dazzling whiteness of the snow. Over our heads they were suspended like crystal chandeliers, long stalactites of ice, or like a magnificent waterfall that had suddenly frozen. The weather was admirable, the sky pure, the air calm, hardly any clouds were visible to the west; Our view discovered an immense extension, and in such an extraordinary position we felt the most alive. We were then at an altitude of 6004 meters, that is to say at the highest elevation, as I believe men have reached in the mountains...

Travels amongst the Great Andes of the Equator (1892), Edward Whymper

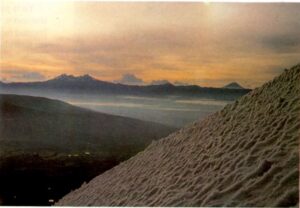

At 5.35 a.m.2 on Jan. 3, we left the tent, and, scrambling through the shattered lava behind it, crossed the arete and emerged on the western side of the ridge. There was then the view before us that is given on the opposite page. The western dome, which had been hidden during part of the ascent, again became conspicuous; crowning wall-like cliffs of lava, that grew more and more imposing as we advanced. As regards the western summit, there are two series of these cliffs—the upper ones immediately underneath the dome, surmounted by sheer precipices of ice, and the lower ones at the end of a spur thrown out towards the south-west. These lower cliffs are neither so extensive nor as perpendicular as the upper ones, and they are crowned by snow, not by glacier. Our ridge led up to their base, and at the junction there was a want of continuity rather than a distinct breach in the walls. This was the spot which, when examining the mountain on Dec. 21, at a distance of sixteen miles, we had unanimously regarded as the critical point, so far as an ascent was concerned.

Up to this place the course was straightforward. In the in Imediate foreground, and extending upwards for 500 or 600 feet, large beds of snow in good condition covered the ridge. The pinnacle or aiguille near at hand was upon the arete or crest of it, and the two others shewn in the engraving upon were higher up on the right hand or eastern side. The ridge itself appears to be fundamentally an old flow of lava. Rock specimens which were taken in situ at various elevations, though differing to some extent in external appearance, are nearly identical in composition, and I have no doubt that several, at least, of the other principal ridges of this mountain were originally lava-streams. Their normal appearance has been largely modified; much is covered up by snow, the exposed portions have been greatly decomposed and eroded, and lie almost buried underneath their own ruins.

After these convenient snow-beds were traversed our ridge steepened—both as regards its arete, and the angles of the slopes on each side; and became in part covered by pure ice, and partly by ice mingled with small stones and grit. When this conglomerate was hard frozen, it enabled us to ascend without step-cutting; but the debris often reposed uncemented on the surface, and rendered caution as well as hard labour necessary. I found here, scattered over about fifty feet, rather numerous fragments of partly fossilized bones. Sir Richard Owen, to whom they were submitted, pronounced them to be "the bones of some ruminant." The unhappy ruminant most likely did not come there voluntarily, and I conjecture that it was conveyed to this lofty spot, either entire or in part, by a condor or some other bird of prey, to be devoured at leisure.

At 7.30 a.m. we arrived at the foot of the lower series of the Southern Walls of Chimborazo, and the termination of the south-west ridge. Then the axes went to work, and the cliffs resounded with the strokes of the two powerful cousins, who lost no time in exploration, as they had already passed this place on Dec. 29. The breach in the walls (for so it must be termed from want of a better expression) rose at an angle exceeding 50°, and here, for the same reason as upon the arete we had quitted, snow could not accumulate to any depth, and the major part of the daily fall slid away in streams, or tiny avalanches, down to the less abrupt slopes beneath; while the residue, dissolved and refrozen, glazed the projecting rocks, and filled their interstices with solid ice. Thus far and no farther a man may go who is not a mountaineer. To our party it caused only a temporary check, for the work was enchanting to the Carrels after the uncongenial labour in which they had been employed, and during a short time we made good progress— then, all at once, we were brought to a halt. Wind had been rising during the last half-hour, and now commenced to blow furiously. It was certain we could not reach the summit on that day; so, getting down as quickly as possible, and depositing the instruments and baggage in crannies in the cliffs after reading the barometer,1 we fled for refuge to the tent, holding ourselves, however, in readiness to start again on the next morning.

Under the small further diminution in pressure which was experienced this day (seven-tenths of an inch), no very marked effects ensued. The most noticeable points were the lassitude with which we were pervaded, and the readiness with which we sat down…

We again started from the third camp on January 4, at 5.40 a.m. The morning was fine and nearly cloudless, and profiting by the track made on the previous day we proceeded at first at a fair rate, and finished the escalade of "the breach" at about eight o'clock. Then bearing away to the left, at first over snow and then over snow-covered glacier, we mounted in zigzags, to ease the ascent. The great schrunds at the head of the Glacier de Thielmann were easily avoided; the smaller crevasses were not troublesome; and the snow was in good order, though requiring steps to be cut in it. Jean-Antoine Carrel led, and my orders to him at starting were that we were to go slowly—the rest was left to his discretion. I noticed, at this stage, that his paces got shorter and shorter, until at last the toe of one step almost touched the heel of the previous one. At about 10 a.m., at a height of 19,400 feet, we passed the highest exposed rocks, which were scoriaceous lava, apparently in consolidated beds, and for some distance farther we continued to progress at a reasonable rate, having fine weather and a good deal of sunshine.

At about 11 a.m. we fancied we saw the Pacific, above the clouds which covered the whole of the intervening flat country; and shortly afterwards commenced commenced to enter the plateau which is at the top of the mountain, having by this time made half the circuit of the western dome. We were then twenty thousand feet high, and the summits seemed within our grasp. We could see both,—one towards our right, and the other a little farther away on our left, with a hollow plateau about a third of a mile across between them. We reckoned that in another hour we could get to the top of either; and, not knowing which of the two was the higher, we made for the nearest. But at this point the condition of affairs completely changed. The sky became overclouded, the wind rose, and we entered upon a tract of exceedingly soft snow, which could not be traversed in the ordinary way. The leading man went in up to his neck, almost out of sight, and had to be hauled out by those behind. Imagining that we had got into a labyrinth of crevasses, we beat about right and left to try to extricate ourselves; and, after discovering that it was everywhere alike, we found the only possible way of proceeding was to flog every yard of it down, and then to crawl over it on all fours; and, even then, one or another was frequently submerged, and almost disappeared.

Needless to say, time flew rapidly. When we had been at this sort of work for three hours, without having accomplished half the remaining distance, I halted the men, pointed out the gravity of our situation, and asked them which they preferred, to turn or to go on. They talked together in patois, and then Jean-Antoine said, "When you tell us to turn we will go back; until then we will go on." I said, "Go on," although by no means feeling sure it would not be best to say "Go back." In another hour and a half we got to the foot of the western summit, and, as the slopes steepened, the snow became firmer again. We arrived on the top of it about a quarter to four in the afternoon, and then had the mortification of finding that it was the lower of the two. There was no help for it; we had to descend to the plateau, to resume the flogging, wading, and floundering, and to make for the highest point, and there again, when we got on to the dome, the snow was reasonably firm, and we arrived upon the summit of Chimborazo standing upright like men, instead of grovelling, as we had been doing for the previous five hours, like beasts of the field.

The wind blew hard from the north-east, and drove the light snow before it viciously. We were hungry, wet, numbed, and wretched, laden with instruments which could not be used. With much trouble the mercurial barometer was set up; one man grasped the tripod to keep it firm, while the other stood to windward holding up a poncho to give a little protection. The mercury fell to 14-100 inches,1 with a temperature of 21° Faht., and lower it would not go. The two aneroids (D and E) read 13-050 and 12-900 inches respectively. By the time the barometer was in its case again, it was twenty minutes past five. Planting our pole with its flag of serge on the very apex of the dome, we turned to depart, enveloped in driving clouds which entirely concealed the surrounding country.

Scarcely an hour and a quarter of daylight remained, and we fled across the plateau. There is much difference between ascending and descending soft snow, and in the trough or groove which had already been made we moved down with comparative facility. Still it took nearly an hour to extricate ourselves, and we then ran,—ran for our lives, for our arrival at camp that night depended upon passing "the breach" before darkness set in. We just gained it as daylight was vanishing, and night fell before it was left behind; a night so dark that we could neither see our feet nor tell, except by touch, whether we were on rock or snow. Then we caught sight of the camp fire, twelve hundred feet below, and heard the shouts of the disconsolate Perring, who was left behind as camp-keeper, and stumbled blindly down the ridge, getting to the tent soon after 9 p.m., having been out nearly sixteen hours, and on foot the whole time…

Montañas del Sol, written by Serrano, Rojas and Landazuri

Augusto Nicolás Martínez: Ecuadorian scientist, climber, farmer, researcher and educator, Ambato 1860 - 1946.

On April 20, 1906, I made my first attempt to ascend to the summit of Chimborazo, accompanied by Juan León Mera I and Pablo Saá Borja de Ambato; but due to the lack of prior preparations, we failed in our attempt and were forced to return from a height of about 6000 meters above sea level, for not having been able to cross the wall of rocks that interrupts the path to the summit. But, in the second attempt, the most complete success crowned my efforts, and I am proud to have placed my plants on the most thematic summit of the King of the Andes, accompanied by Miguel Tul, a purebred Indian, whom I had exercised in advance for this kind of sport. Below I give some details of my ascent to the famous snow-capped mountain.

You must have already known that my fellow travelers were the estimable and friendly French gentlemen , Mr. Paul Suzor, and Dr. Pierre Reimburg; but what they surely ignore is that with these gentlemen I had a formal commitment, from months ago, to accompany them on an ascent to the Chimborazo, and if we had not done it before, it was because we first tried to acquire the material of ascension, We lacked... So, our first care was to ask France for real and legitimate ice axes, crampons, gloves, glasses, etc. all of which could not arrive until the first days of January.

In addition, as it was to climb a mountain of difficult access and very high, and as I wanted to ensure, as far as possible, success, I advised my colleagues to try to exercise their muscles and lungs , making some ascents to the Pichincha: I, for my part, did not neglect that precaution either, and in the months of October to January, I ascended three consecutive times to the Tungurahua, with which I acquired a magnificent entrainemaint, as the French say.

These climbs also helped me to discover a courageous and determined companion in every way, in the Indian Miguel Tul ; because in them he showed himself as a man devoid of nerves and of a truly wonderful resistance...

On January 16, 1911, Messrs. Paul Suzor and Dr. Pierre Reimburg arrived in Ambato, the former being charged d'affaires with France and the latter with a scientific mission for the government of the same nation, with whom he had contracted, months before, a formal commitment to attempt the ascent of Chimborazo.

On the 17th we moved to the “Cunungyacu” hacienda located northwest of the snowy mountain; On the 18th we set up our camp at an altitude of 5,150 meters in the same place that the famous German traveler, Professor Hans Meyer, had his camp 8 years before. As Dr. Reimburg was attacked by a terrible soroche the same afternoon we arrived at the camp, we were not able to make the ascent on the 19th, hoping that he would improve, but nevertheless, we took advantage of the time, climbing with Mr. Suzor and our two pages, to the waist of rocks that stopped me on the previous trip, in order to look for a practicable pass between them, since I was convinced that once that difficulty was overcome, success was certain. Indeed, we found a very favorable and not very dangerous place and we returned to the camp again from a height of 5,900 meters.

On the 20th, at 4:30 in the morning, we began the ascent, but without Dr. Reimburg, who had not improved; Three hours later we happily passed the belt of rocks and found ourselves on the immense Stübel snowdrift, located northeast of Chimborazo. At the height of 6,040 m, Mr. Suzor was forced to give up going forward, because he felt that the toes of one of his feet had frozen, and to my great regret, I had to leave him there, in the company of his page, Manuel Cárdenas. I continued the ascent only accompanied by Miguel Tul, and a quarter of an hour later we found ourselves stopped by a wide and deep crack that crossed the frozen slope, which we crossed over a flimsy ice bridge; At that moment the needle of the aneroid barometer arranged to measure heights below 20,000 feet (6,096 m) became motionless. At 12 noon we crowned the Veintimilla summit, 6,220 meters above sea level.

We have ahead a slope of something more than 100 meters that it's necessary to raise; but again the snow doesn't offer consistency and we climb painfully: a little and taking rest every eight or ten steps I go up, until at last I am at the top of the Chimborazo. With a certain fear I direct the look everywhere, because I fear having to climb even more; but no, I am in the true top and nothing is higher in the contour. It's 12 and 55.

Impossible to describe the impression I feel when stepping on the summit of the King of the Andes : it's a mixture of taste, satisfaction, amazement at seeing my efforts crowned and also why not say it? of pride because how many had tried to reach, as far as I have placed my feet, except Whymper and maybe Usuelli, they were forced to give up their business.

At the summit of Chimborazo, which is located, according to the French geodetic mission, at 6,270 m, I remained for half an hour trying to see something of the immense panorama that must be enjoyed there, which, unfortunately, was hidden by a sea of clouds that It extended to the last limits of the horizon, except only towards the Northeast, in which direction I could see some moors and in an immense distance, a blue horizon that merged with the sky, which I believe was the sea. Towards the north of the immense sea of clouds, the summit of Cotopaxi stood out like a distant island, crowned with a plume of black smoke; and to the east, some snow-capped peaks of Cerro Hermoso, that's all I could see from there.

After having firmly stabbed my companion's cane and tied one of the four pants that he was wearing to it, so that it would be visible from a distance, since the flag was forgotten with Mr. Suzor, We began the return and after three hours of constant descent, we arrived at the camp at 5 in the afternoon, where we found only Mr. Suzor, since Dr. Reimburg had descended to the ranch after having observed my arrival with the telescope. to the Veintimilla summit, the only one visible from the camp.

Three days after we were at the northern foot of the great Chimborazo, thanks to a completely clear morning, my two companions were able to see, with their glasses, Miguel Tul's pants at the summit of Chimborazo.

American Alpine Club

Little more than a day after our departure from Iliniza, we found ourselves at the end of the jeep trail on the northern slope of Chimborazo. Though the weather was less than perfect, it was incomparably better than the Iliniza variety. We could see far enough to study possible ascent routes. Evidently, there was only one fairly safe line, free from the dangers of falling ice and avalanches, the northern ridge. Its lower part was sharp and pronounced and did not appear too difficult. Higher up we expected technical difficulties where the ridge ended under a several-hundred-feet-high ice barrier, which goes all the way around the north side of the mountain. It was evident that we would need several camps above our 14,000-foot roadhead, which was still a couple of miles away from the proper base of the mountain.

For two days we carried loads to establish an advanced base camp at 15,300 feet and a cache at 16,500 feet. Our advanced base was a lovely place at the foot of a giant moraine. Water trickled from the rocks and the last struggling outposts of vegetation surrounded us.

On August 8, all of us moved to a higher camp, slightly above 17,000 feet. That afternoon George Barnes and Bill Ross set out to explore the great ice barrier. Meanwhile, the rest of us brought more supplies to Camp I, a small platform between the edge of the glacier and a steep frozen slope with none of the friendliness of our last camp. George and Bill brought good news in the evening. They had found a route through the icefall and reached a point from which comparatively easy slopes led to the summit. From there on, the rest was mainly a matter of determination.

The next day, carrying loads of 50 to 60 pounds, we all began to feel the altitude but were in high spirits because of the second straight day of fine weather. Around noon we reached the icefall. The first few rope-lengths were just as steep as they had looked from below. This cliff was composed of the strangest material. It was not ice, nor one of the 23 sorts of snow known to science. It must have been that sweet stuff: meringue, made from sugar and egg whites. Oh, Lord! How tiring it was to climb a 60° meringue-slope with a heavy pack at 18,000 feet. Close to exhaustion, we reached a great crevasse just above the icefall. That was to be Camp II. We descended to the bottom of the crevasse and after testing the bottom, set up both our two-man tents. It seemed ideal— level, roomy and well protected from the wind. A little later we had to change our opinion. Had we, by mistake, set up camp in a supersonic wind tunnel?

The following morning intense cold and an immaculate sky promised more gorgeous weather. This was to be the summit day! Shortly after seven o’clock we left camp, dressed in all our clothing. There were a few big crevasses and some minor problems of route finding but the rest was toil and monotony through more of the meringue. The first man broke trail but did not leave a packed trail behind him.

At 1:30 we dragged ourselves up the last slope of Chimborazo’s north peak. Ecuadorian climbers had told us that this summit was previously unclimbed. True or not, it hardly deserved to be called a peak; north shoulder would be a more appropriate name.

After the fog had lifted, in which we had spent some fifteen minutes, we noticed another, higher peak to the south. For a moment we were confused. Was that the main peak over there? Or had we not even reached the north summit? Whatever it was, we would climb it. After another hour of toil, we reached the top of a vast, almost level plateau, half the size of a football field. There was no higher peak. Hurrah!—we had scaled the highest mountain in the world, higher than Mount Everest —if you measure from the center of the earth!

The trip back to Camp II was uneventful. During the night a terrible storm came up, robbing us of our sleep. The next morning everything was covered with fresh snow and rime. Visibility was poor and the wind was still blowing fiercely. We broke camp and descended immediately. Taking with us only the more valuable things from our lower camps we arrived at the car at five P.M. What do you think, comrades, about driving tonight to the city of Ambato, there to enjoy the hospitality of the Hotel Florida?

Revista Deportes sin Límite, July 1983. Author: Rómulo Pazmiño.

The Grouping Excursionist New Horizons, in commemoration of the bicentenary of the birth of Simon Bolivar, organized an ascent to Chimborazo, mountain whose beauty and grandeur inspired the Liberator his famous Delirio. This ascension would go from east to west passing over all the summits of the colossus, that is to say, it was a matter of doing what in alpinistic terms is called an integral. The arrival at the peak was planned for Sunday, July 24. Everything presaged the success of the company, but an unexpected change of weather conditions determined another reality...

THURSDAY, JULY 21

Dawn surprises us arriving in the city of Riobamba, in the middle of a light but persistent rain. The pickup truck previously hired is waiting for us and after a small breakfast we embarked towards the mountain.

The group includes Carlos Cevallos, Jorge Castillo, Maximiliano Yépez and Rómulo Pazmiño. Each one has shown optimal physical, technical, psychological and interrelation conditions; it's therefore a strong and homogeneous team. According to the initial plan, we must spend 4 days touring all the Chimborazo summits.

From Riobamba we go to Chuquipogyo where we leave the asphalt and we go through fields of mellocos, peas, beans and barley. The poor condition of the road prevents our vehicle from exceeding 3,700 meters ; so we spread the load between the 4 and we start the march full of enthusiasm despite the drizzle.

When the first blade dominates, a momentary confusion arises: we see nothing. The mountain is somewhere hidden in a thick bank of clouds. We connect our autopilot and, following hills and streams, we begin to gain altitude through the moor, trying, yes, to avoid unpleasant encounters with wild cattle. At 5 o'clock in the afternoon we decided to camp in a strong blizzard at a height of 4,800 m. For our fortune, the Nicolás Martínez peak is cleared for 5 minutes, allowing us to verify that we aren't too far from the route that we initially imposed.

FRIDAY, JULY 22

After enduring a cold and windy night, we disarmed the camp and re-started the march at 9 in the morning by a long and steep blade covered with frost. The landscape is icy, a dense fog envelops everything and the blizzard whips mercilessly our faces. The advance, although constant is slow due to the large amount of fresh snow.

Upon reaching the base of the mountain we decided to flee from the storm that hits us from the northeast and we undertake a long journey to the south side. At noon we put on the crampons and form two cordadas : the first with Rómulo and Carlos and the second with Max and Jorge. We started climbing ice, snow and rock slopes until we reached a platform at 5,100 m. Tall; you can not see beyond 20 meters, only the instinct and the experience guide our steps through these solitary places unknown to us. The crossing continues at the foot of some large rocky cliffs from whose height fall avalanches of powder snow that leave us breathless. We continue advancing without knowing very well where. Suddenly I discover a step that seems to lead upwards. it's 4 o'clock in the afternoon, we are climbing a steep slope of fresh snow, but consistent due to the low prevailing temperature; the heavy backpacks force us to concentrate on even the smallest movements. We are gaining height. At 6 we stop to build a platform where to install the store. Our second camp looks more like a loft hanging from the tower of an ice cathedral ; downward unfathomable cliffs and over our giant stalactite heads that threaten to detach at any moment.

Sleeping? ... Impossible! Fortunately dinner is excellent and good humor doesn't decline. The music that flows smoothly from Carlos's flute caresses the flanks and gorges of the mountain, as if trying to tame it, and at the same time comforts our spirits.

SATURDAY, JULY 23

We restart the climb at 9 in the morning, first on the left, but the pass is cut by cliffs. We then turn to the right at the base of the wall until it borders on the east and we straighten our course towards the summit, following a long and pronounced corridor that places us at the foot of the Pico Nicolás Dueñas. The conditions of visibility are very variable. We continue the ascent to a platform where we rest a few minutes and, finally, for a blade of very soft snow where we sink to the knees reach our first goal: the summit Nicolás Martínez, of 5,460 m. It's 2:30 p.m.

We return lightly on our tracks and we immediately start our descent towards the pass between the Martínez and Politécnica peaks. Incredible descent , the fog blurs the light and suppresses any shadow, making us lose all notion of distances and proportions.

The slope of the Polytechnic summit is soft, but exhausting due to the loose snow. In the last section Max is suspended suddenly over a crack, the edges begin to fall apart...! Happily we are close and we can help you right away.

it's 6 in the afternoon and we are almost on top of the Polytechnic Summit. The wind and the cold are unbearable; Despite the feather clothes and good shoes, we began to feel freezing principles. We must stop. The moon appears at the moment of finishing installing the store. The temperature is very low, about 20 degrees below zero ; there is no way to detach the leggings that the ice has welded to the boots.

SUNDAY, JULY 24

At 9 o'clock in the morning we are on the way again and in a few minutes we reached the top of the Polytechnic summit, 5,820 m. We started to descend; the fog makes us drift towards the edge of the cliffs on the southern side of the mountain, but we notice the danger in time and correct the course towards the maximum summit.

it's our fourth day of ascension and fatigue and dehydration aren'torious. The physical effort at almost 6,000 m. of height it produces an accelerated wear, we advance very slowly. To quench the thirst we drink a liter of dextrose of low saline concentration that we take from our medicine cabinet and that is pleasant. Arriving under the great barrier of seracs and cracks that defends the summit, we decided to camp; it's early still, the 16 hours, but we think it's better to rest well because tomorrow we expect a long and hard day. We are worried, today we had to have descended to the Whymper shelter, our friends must be alarmed...

MONDAY, JULY 25

Sleep at 6,000 m height is always a demanding test, but the group has responded well; Apart from a slight headache that is relieved with an aspirin, no discomfort. The recent experience of my colleagues in the crossing of Cotopaxi has prepared them properly.

We leave at 8.30; the backpacks weigh less and, finally! , the sun shines. We skirt the barrier of seracs by the north until we find a passage through which we dominate a first level, but we don't pass here... new obstacles extend transversely as far as the eye can see. We return on our footprints towards the central part and after much searching we finally discover a diagonal cornice that offers possibilities. With the care of a surgeon and almost without breathing, we open a paddle in the fragile structure of ice, where with a lot of skill we passed one by one. We then find more consistent terrain that allows us to ascend faster; one last rimaya and, suddenly, we are under the radiant dome of the main summit.

After 4 days of walking almost blindly, so much light and color dazzles us. The mountains of the country have been stripped of their cloud cover to greet us, there are all, from Cotacachi to Sangay, splendid and haughty... impossible to ask for more!

At each step the snow creaks and gives in abruptly, causing us to faint. Only knowing that we are fighting the last battle encourages us to continue. One more effort and... Thanks to God! ... we finally reach the peak of Chimborazo. it's 17:30 hours, we are 6,310 m. high above sea level. We embrace excited.

We have triumphed, but we still have the descent. Despite the radiant sun, the cold is intense. We descend to the hill between the Whymper and Veintimilla peaks to install our last camp at 6,200 m. The day dies when we get into the tent...

TUESDAY, JULY 26

We consume the last provisions: cookies, jam, some tea and some candies. We are very tired and have a hard time getting up. It's 10 in the morning. Suddenly... aviones! ... 2 jets pass very close stunning us with their thunderous noise... they come again! ... we greet them jubilant ... they have seen us!...

Quickly disarm the camp and get going. It took us two long hours to dominate the Veintimilla summit, the snow is tremendously soft, and without stopping we started the descent towards the Whymper refuge. As we looked to the head of the glacier we observed 4 climbers climbing the ridge; we assume that they are partners of our Association that come to help us. Indeed, it's a rescue group commanded by Julio Tinajero and Hugo Carrillo. Tears of excitement from part and part. We continue downhill and already very close to the shelter I can hug my father and my brother René. The adventure has ended happily.

Tired but happy we are ready to depart for Riobamba, when a helicopter appears that after flying over the mountain perches very close to where we are. From the cabin Leonardo Droira descends, his face reveals the joy of finding us safe and sound; He informs us that this morning's planes did not see us, so he decides to leave immediately, bringing the good news to our relatives and friends.

As we descend the road towards the city, we turn a moment to contemplate the majestic mountain. We have never seemed so beautiful...

Revista Campo Abierto No. 13, October 1990. Author: Iván Vallejo.

On December 27 at 8 in the morning we untied the ropes at the foot of the ridge and as in every beginning of climbing there was a mixture of anxiety and emotion in the environment.

I still felt in my heart the rhythm of "To my God I owe everything to you", the best song of Joe Arroyo, the parties of Quito, of Christmas, Chayane and the discotheque.

The idea of this escalation arose one day when we were talking with Ramiro about the book "La integral de Peuterey". -We can also do something similar here. He said, with his characteristic way of saying the things he considered important. -Where? I asked with some astonishment. - The integral of the Chimborazo by the Arista del Sol.

We began to plan how to carry out this beautiful journey. We will do it "superlight" . "This is: no tents or camps, only the bivouac holster, a reverberant, a pot, some food, but very little, and at night water. Much water.

But life is so. This way will remain, forever, waiting for your footsteps and your voice.

Now we are Oswaldo and me. When I phoned him to disturb him, it took me longer to tell him than to accept.

Of the "superligeras" backpacks, they weighed me to the seams, and what was there in them? We had only put the bivouac bag, the sleeping bag, the dehydrated food, a stove and some other thing. of the problem.

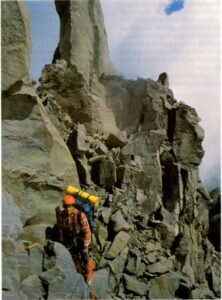

The ridge is a beautiful climb. Its rock, without being the best, is good, although one day whole towers could fall, tired of keeping balance for so long.

We took the lead. On more than one occasion we had to retrace the steps to avoid an artificial or an air pass on a ledge. Already in the march we were going hand in hand with tapes. Nuts, fingers, hands, that is, what works.

A month or so ago Willie Navarrete and Lucho Naranjo climbed this road, until Nicolás Martínez, in five hours. Go they flew! and they had explained where to take each place. Today it's evident that the route has changed a lot and the five hours they did a while ago happened to us.

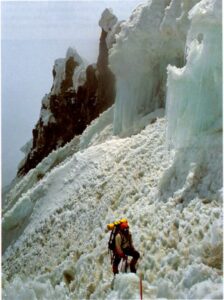

It's almost six in the afternoon when we enter the ice. Oswaldo tries a dozen times to get into a loose snow runner, everything collapses under his feet, he can not hold on to anything. In the end, more with courage than with technique, he manages to get out and place a screw to rest. In the next long I'm lucky; it's a beautiful ice, very hard but clean.

At 6:30 am the anger reaches its maximum expression. We have been climbing for ten hours "superlight" and we are still on the edge and worse, we don't know where the fuck will be the exit. For today the film is over, I don't know how they did it in five hours.

FIRST VIVAC

It's a small, uncomfortable shelf, hanging on the wall. We have to ensure everything: cameras, helmets, illusions and joys, lest they fly straight to Chuquipogyos.

That of getting into these conditions inside the sleeping bag, moving what is strictly necessary to prevent something from falling and getting as comfortable as possible against the rock to prepare to prepare a comforting soup is a rite and takes time. But, with what water do we make the soup? We had neglected the supply of snow to melt and the nearest snowfield was twelve meters higher after climbing a corridor. With all that had cost to pack me in the bag and accommodate the ribs to the cracks of the rock.

It was a beautiful night. I understood Rebuffat when he talked about the bivouacs and tried hard to fix in my memory at least the names of the constellations that Oswaldo showed me: from Orion the belt, the sword, this and other. At times I fell asleep and at times reviewed the lesson of astronomy.

THE NICOLAS AND THE POLI

There was no doubt that everything has changed since I was last here. A stake of the "superfasters", which at first filled us with joy, has confused us completely and we are climbing on a tenacious ice of a ramp that hangs over the void like a glass balcony looking at the Polytechnic .

We have been climbing for almost three hours and we don't have the exit. Where the hell Willie will have gone up? He told me to always take the right and we are giving it to the right. Until finally, two longs to the left and we left.

Near the summit I remembered the ugly experience of last year. We were also trying the integral. It would be six o'clock in the afternoon when, just as I was about to shout to my comrades that we were already on the Nicolás Martínez, everything collapsed under my feet with a loud bang. They would have to spend almost three hours until they hugged my companions who helped me out of that ice tomb.

Now it was 13h30. Oswaldo guessed my thoughts and realized that I should be afraid of such memories, but with a hug he knew how to restore my confidence so that I could enjoy our first summit along the ridge and -superligeros-.

From the Nicolás to the Poli, apart from the fright of seeing my companion disappear in a crack, there were no major setbacks and at 3:30 p.m. we placidly let the wind drown us by hitting our faces on the second summit.

What a beautiful place. So immense and beautiful and, modestly, just for us. We went to the Maxima looking for the northeastern flank, because with my experience of last year I could see that the crack of the summit if it was not the same, it was even bigger.

At 17h00 we declare ourselves in * total madness * and that's where the climbing day ended to begin with the rite of the bivouac , accommodate the ribs to the rope and make water. While we melted snow, we talked about the things that are spoken at 6000 meters: the house, the bride, the great friends.

In the midst of so much peace and so many stars the damned reverberation occurred to him to explode. The bivouac bag burns, the mattresses burn, the water is watered, everything gets wet... A thousand times shit of reverberation!

TO THE MAXIMA

On the right there is no such. They are seracs who expect you to watch them to declare themselves in favor of Newton's law. Without more we retrace our steps and we go towards the huge crack. It's the same as last year, immense, huge. For a moment I think of my son Andres, surely he with the baton Io would solve everything, but now we don't have the anchor or Batman is with us. But Oswaldo finds the solution.

With his characteristic stubbornness of not wanting to go back until he did not try or investigate everything, he managed to find the longed-for step.

Between insurance, strings and songs we got 18h30. We started climbing the wall but decided to stop. Total, tomorrow we will see what remains to be done. A hole dug in the ice gave us shelter for that night.

YES NOW. AT LAST

With Franciscan patience we were able to obtain, in four hours, half a canteen of water. It was not bad, but not good for a couple of hungry and thirsty dead as we were at that moment.

On us was the wall of ice and a journey through some -tubes- of ice. That trip was fantastic : ice of a limpid and transparent blue, two tools and two tips, screws, rope and insurance. I was happy for what it was, what I was doing and knowing what we were going to get.

At last the slope was dying and with it we were losing also that force full of lucidity that we had until shortly before. Knowing that we only had to walk in wait for the horizon to be flattened, we suddenly reached the accumulated fatigue of the last four days with his three bivouacs.

The last few meters were infinite but wonderful. We were doing it. More happiness could not fit in me and I thanked God in the manner of Joe Arroyo: Oh Dad, how I love you Dad!

At 3:30 pm the summit. I never felt so beautiful, so great, with so much energy. Unable to hold back the tears I hugged Oswaldo, my friend and fellow adventurer.

Looking at the sky, which was infinitely blue, I thought of the Ramiro. Thanks ñañón. I know that you were with us all the time and if we succeeded it was for you and in your name.