Carta del Dr. W. Reiss á S.E. Presidente de la República, Gabriel García Moreno

Wilhelm Reiss (13 June 1838 – 29 September 1908), German geologist and explorer

Already in the year 70, together with Dr. Stübel, we had visited the Corazon and admired the deep caldera that encloses this volcano ; but it was not possible for us to descend into this gap from the point of our observations. To get to know this caldera, I visited the southwest side of the Corazon, from where, without much work, I reached its bottom. This caldera that is the deepest I know in Ecuador , is surrounded by rocks at least as steep as those of the Pichincha crater. Deeper than the Pichincha crater, but not as deep as the caldera of the Corazon, it's the caldera of the Rumiñahui volcano that can be seen from the royal road between Machache and Tiopullo. Everything else; craters and calderas, with the exception of Antisana, have insignificant depths compared to those of the Corazon.

I have taken here the height of the Corazon, as it turns out from my trigonometric observations, as two measurements, the one from the year 70, the other from November 72, also gives me the peak of the mountain a little more than 4800 meters: consequently about 30 meters more than barometric observations.

During my visit to the Corazon the sky was very clear, and several times I have seen the hills that extend to the West, almost to the plains of the sea, and particularly the valley of the Curiyacu River beyond its confluence with the Toache River, and I must confess that you can seldom find a more purposeful terrain for a road, than this beautiful valley.

In the middle of the immense hills that surround it, the heights called "Cerritos de Chaupi" almost disappear, however it's a volcanic mountain that in any other part of the world would be considered as tall and large. Almost from all sides there are three cusps that seem to form a small mountain range; but in truth these are the highest points of the walls of a rather large caldera, called "Hondon de San Diego"; that drains on the north side, joining the Curiquingue river with the waters that pass through the Jambeli bridge. The eruptions that this volcano has made have caused almost a meeting between the Rumiñahui and the Iliniza, thus breaking the continuation of the deep valley that stretched between the two ancient mountain ranges and which today filled with volcanic ejections form the plateaus of Machache and Latacunga .

Travels amongst the Great Andes of the Equator, Edward Whymper

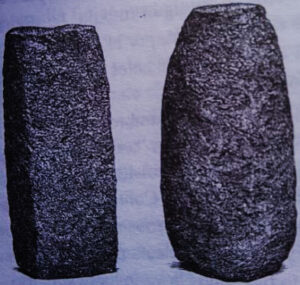

Carved stones found at the Corazon summit.

Certain circumstances led me to say in the morning, "Señor Racines, now tell me, upon your word of honour as a gentleman, Are there fleas in this house?" There was just a fractional hesitation, and then the tambo-keeper answered with the air of a man who spoke the truth, "Señor, upon my word of honour, there are." The information had been confirmed beforehand. It was decided to have a general clear out, and Jean-Antoine, to his credit, became chief housemaid. The contents of our apartments were taken into the gallery of the courtyard, and were scrubbed, brushed, beaten or shaken, much to the wonder of the natives. The news spread, and soon the patio was filled with a troop of sallow urchins, grinning from ear to ear. "These gringos are very odd," they said. "See! that is the Seilor patron. Look!"—pointing to Jean-Antoine—"that is Senor Juan. What a fine beard!"…

Illiniza was obviously the loftiest of the several mountains which have been enumerated, and I sent Jean-Antoine on Jan. 29-30 to reconnoitre it; but as he reported that it was nearly inaccessible from the north we turned our attentions to Corazon, at first ludicrously under-estimating its distance. We went out late one day, expecting to reach the top and come back again, and did not even get to the foot of the actual peak. This, however, was a red-letter day—we saw a dead donkey, under a hedge about 1500 feet above Machachi; and a few hundred feet higher met a scorpion who was coming downhill.

Corazon was ascended a century and a half ago by La Condamine and Bouguer. The former says expressly (at p. 58 of vol. 1 of his Journal du Voyage) that they made the expedition upon July 20, 1738.2 In the prosecution of their work, they encamped twenty - eight days somewhere upon the mountain (doubtless upon its eastern side), but there are no precise indications of the route which was taken by them, nor could any information be obtained at Machachi, though a certain Ecuadorian named Lorenzo vowed that he had been to the top. This man was engaged to act as our guide.

The mountain Corazon has received its name from a resemblance it's supposed to have to a heart. it's a prominent object from Machachi, placed almost exactly midway between Atacatzo and Illiniza. Its slopes extend to the outlying village of Aloasi, and after rising gently and then abruptly lead one to easy grass land, which continues uninterruptedly to the foot of a cliff about 800 feet high, that is found at the top of the mountain. With trouble, one might ride, upon the eastern side, to within a thousand feet of the summit. On some days the mountain was almost covered with snow down to 14,500 feet, and on others no snow whatever was seen on any part of it.

Lorenzo led us to a place a long way to the south of the summit, and then evidently came to the end of his knowledge. On his "ascent" he had gone as far as one can go with the hands in the pockets, and had stopped when it was necessary to take them out.1 We continued in the same direction to see what the western side was like, and presently put on the rope. Our guide was the first to be tied up, and, though he said little, his face expressed a good deal. Possibly he supposed that he had been inveigled to this lonely spot to be sacrificed on the cairn of stones put together by Jean-Antoine, which bore a suspicious resemblance to an altar.

The western side of the highest part of Corazon, like the eastern side, is formed of a great cliff. Snow gullies run up into it, and one of these, towards the south end of the ridge, seemed to promise easy access to the summit. We had only progressed a few yards on this couloir when the clatter and buzz of falling stones was heard, which lew down- at a tremendous pace, quite invisible as they passed by. We retired under cover of some rocks to read the barometer,2 and then returned to the south end of the peak, skirted the base of the eastern cliff, worked round to the north side, and ascended by the ridge that descends towards Atacazo. The route on this day was unnecessarily circuitous, and is not given on the map. The ascent of Corazon can be made most easily by taking the line we followed on Jan. 27, as far as we went, and completing it in the same way as upon Feb. 2. The track on the map combines portions of the routes of these two days. The upper part of Corazon is a great wall, roughly flat on the top, which is, I believe, a dyke—a mass of lava that has welled up through a fissure. At its highest, it's nearly level over a length of 250 feet, and is only a few yards across from east to west.1 At 1.15 p.m., on the highest point, the mercurial barometer read 16 •974 inches, at a temperature of 43° Faht. The height deduced (15,871 feet) is slightly greater than that assigned to the mountain by La Condamine (2470 toises), and by Reiss and Stubel (4816 metres). The extreme difference between the three measurements amounts to seventy-five feet.

There was on the summit an indication of a previous ascent in two dressed fragments of rock, about nine inches long, which caught the eye directly we arrived. They were a black, scoriaceous lava, similar to the highest rock obtained on Chimborazo, and subsequently on various parts of the cone of Cotopaxi. I saw no natural fragments of it on Corazon, and therefore conclude that these dressed pieces must have been transported some distance by the person or people who left them in the place where we found them.

The rock of the summit is described by Prof. Bonney as an augite-andesite, and closely resembles examples from several of the mountains which will be referred to in later chapters. Its natural colour is a slaty-grey, but this is only apparent in newlybroken, unweathered fragments. Surfaces which are exposed to the atmosphere become a dull red (approximating to indian red), and this colouring doubtless arises from the rusting of the iron that is present in these lavas.

The summit ridge was by no means exclusively rocky. The scoriaceous surfaces, by decay, had been converted into soil, and in the earth so formed there was quite a little flora. I collected five lichens and as many mosses, three Drabas, a Lycopodinm, a Werneria, and an Arenaria. These were growing upon the very apex of the mountain, and from their abundance and vigorous condition it was clear that most if not all of the species might have attained a considerably greater elevation if there had been higher ground in the vicinity. From amongst this vegetation, I disinterred an earthworm, a beetle, a bug, and some spiders. Several species of flies were seen on the ridge, but I only succeeded in capturing one…