Nevados de Ecuador y Quito Colonial, Ángel N. Bedoya Maruri, 1976

Humboldt's Last portrait with the Chimborazo, by Julius Schrader, 1859. Metropolitan Museum of Art

it's the Cotopaxi the highest of the volcanoes of the Andes that in recent times has suffered eruptions. Its absolute height of 5,757 m. is double that of the Canigou exceeding by so much 800 meters the one that would have the Vesuvius located over the peak of Tenerife. it's also the Cotopaxi the most feared of all the volcanoes of the Old Kingdom of Quito for its strong and devastating eruptions. A colossal mountain would gather together the slag and portions of rocks thrown by this volcano and that cover the nearby valleys in an extension of many square leagues.

The most beautiful and regular of all the peaks of the Andes is that of the Cotopaxi, a perfect cone that is covered with a huge layer of snow, shines at sunset, and stands out picturesquely from the bluish vault of the sky...

Only from very close to the edge of the crater are some banks of rocks that are never covered with snow and that from a distance appear black lines, a phenomenon that must be attributed to the rapid slope of this part of the cone and the cracks that give off a warm air current to the exterior...

In Cotopaxi it's difficult to reach the lower line of the perpetual snows, due to the deep cracks that surround the cone and drag in the eruptions to the Napo and Alaques rivers, slag, pumice, water and ice floes. We checked this difficulty personally in 1802. Examining the volcano closely you can be sure that it doesn't allow it to reach the edge of its crater.

Given the regularity that affects the cone of this volcano, it's surprising to find the southeast and half hidden by the fog, a small reddish mass bristling with tips that the natives call Cabeza del Inca ; denomination of uncertain origin, and founded on a popular tradition that claims to have gone this rock once part of the Cotopaxi; the Indians assure us that the volcano launched in its first eruption a stony mass that covered the enormous cavity of the underground fire.

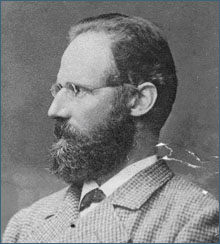

Carta del Dr. W. Reiss á S.E. Presidente de la República, Gabriel García Moreno

Wilhelm Reiss (13 June 1838 – 29 September 1908), German geologist and explorer

...The firm rock was less tiring than the unsafe floor of the sand, and here we could walk without constantly attending to the stones that detached from the rocks of the summit, descended in immense jumps along the sand and whistled like bullets; crouching a few times, jumping others to my side and another, we avoided being hurt by many of these stones that falling more than 300 meters high, and sometimes big as the head of a man, had enough strength to hurt seriously. Until now I had gone ahead, but seeing that my butler lost his spirit when he stayed behind, let him take the lead and I followed behind. The floor in this last part is very bad, because the broken stones are breaking and crumbling under the weight of man. One of those stones falling down on me, at a point where it was impossible to avoid it, caused me a wound that almost forced me to turn from very close to the top, and that pains still today, after more than one month, it has not healed completely. The peak was wrapped in clouds, and to this cause the rocks we had before us seemed very distant and very tall; but skirting a little on the south side, we suddenly arrive at the top. At that moment the clouds dissipated, and for the first time human eyes probed the bottom of the Cotopaxi crater.

I can not and I don't want to deny that I have been happy to have reached the first climb on the highest of the active volcanoes in the world. A sensation equal to mine was also painted on the face of my companion, Ángel María Escobar of Bogotá, who had achieved a true triumph by climbing to that height suffering a lot from the rarefaction of the air, while I had not felt anything at all. the way. The edge of the crater was covered with clouds that without filling its cavity, passed through the peak of the hill. We had reached the western part of the South lip, next to the southwestern peak, in a part where there was no snow...

...Little was left to get to the rocks of the southwest cusp, which is the second in height. My trigonometric observations, repeated several times from different points and with independent bases; They have given me 5943 meters of height of the cusp of the north and 5922 meters of the one of the southwest. My barometer gave me 5993 ; thus, the results obtained by both methods give much higher heights than those published by previous travelers. it's very probable that the temperature of the air that I have taken in the calculation, is too high; but since probably all the air above the crater has a somewhat elevated temperature because of its hot vapors, it has not been possible for me to obtain better data. The rocks of the southwest cusp are cracked everywhere and vapors of 68 degrees Celsius leave in large quantities with such a strong smell of sulphurous acid that you can not suffer them when the wind takes them to the observer...

...November 28, 1872. Southwest cusp, 0.4C, 11 and 45 a.m. 5992 meters...

...While I was riding on the edge of the crater holding Angel Maria with one hand and examining with the other the deposits of the fumaroles, a gust of wind filled both eyes with sand impregnated with sulfuric acid, causing an inflammation immediate and very strong, whose consequences I have suffered for many weeks. So, almost blind, I could not think of anything else but to get down as quickly as possible. At 11 and 45 minutes we had reached the edge of the crater, and at 1 and 15 minutes we started the descent. Avoiding the hard rocks as we could, we quickly descended on the sand ... A few prickly pears and a little brandy mixed with pieces of ice refreshed us; and happy, and without taking care of a subtle hail, we ran down the sand. A few moments later we arrived at the beginning of the lava, and at 3 and 30 minutes we entered the camp, at the moment when a strong snowstorm began...

...I have shown the way, and that other travelers more skillful, stronger and more fortunate than me, will be able to climb from here onwards to the Cotopaxi crater without encountering the difficulty of the difficulties, that is, with the general conviction that it's impossible to reach him...

...In the relations of climbs to high mountains there is a lot of talk about the influence exerted by the rarefaction of the air . I have not suffered difficulties of this kind in Cotopaxi. it's always difficult to walk in such great heights; but this difficulty begins between 4000 and 4500 meters, and I did not think that it increases with height. In other hills and at lower altitudes I have suffered much more, mainly from a very strong headache and from such lack of breathing that I have believed to drown me. My butler and the pawns who accompanied me in Cotopaxi suffered all these ills, and one of them, a very handsome man, was vomiting in the middle of the road, but none of them got blood from his nose or from any other place. That the animals are subject to the same evils, is demonstrated in the difficulty with which the mules walk in heights greater than 4000 meters; and also my dog, which usually did not seem to suffer, came to the crater complaining a lot and it was necessary to encourage him continuously so that he would not be left behind...

Travels amongst the Great Andes of the Equator, Edward Whymper

Cotopaxi crater, drew by Edward Whymper, 1880

We started from Machachi for Cotopaxi on February 14. The party consisted of Jean-Antoine and Louis, Mr. Perring, six natives of Machachi as porters, nine mules and three arrieros, and a couple of sheep—a pair of ungraceful and graceless animals, who displayed the utmost reluctance to go to the slaughter. They squatted on their haunches and refused to move, and when at last, after infinite persuasion, they were induced to get up, they ran between our legs and tried to upset us....

It was not a very eligible locality, for two of the essentials of a good camping-place—wood and water—were wanting; and one half of my forces went upwards in search of snow, whilst the others descended two thousand feet in quest of scrub, leaving me in charge of the camp, to act as cook, journalist, and cattle-tender. One of the sheep had already been killed, and some of the choicest cuts had been placed in our pots and kettles to be boiled, and I promised my people that when they returned they should have such a feed as would make up for days of semi-starvation. But when they were gone I began to think that I had promised too much, for the fire would not burn, and I had to lie flat on my stomach and blow hard to keep it alight at all. And then snow and hail began to fall, and I found my feet got uncomfortably cold while my head was exceedingly hot, and just at this time I heard a noise, and, looking up, perceived that the other sheep, which had not been turned into mutton, had escaped from its fastenings, and was hurrying down the slope. I gave chase and caught it, and talked to it about the wickedness of attempting to escape. The sheep certainly looked sheepish, but it would not return upwards without much persuasion, and when we got up again I found that the sheep that had been turned into mutton had turned over into the volcanic ash, and had nearly put out the fire. All the broth had descended among the ash, the fire was nearly extinguished, and the meat itself was covered in a most abominable way with a sort of gritty slime. Such nastylooking stuff it has never been my lot to see, before or since; and I almost blush to think of the devices which had to be employed to make it presentable. But all's well that ends well! I came up to time, and my people were never the wiser, though I did clean that meat with our blacking-brush, and wipe out the pots with a pocket-handkerchief.

We hurried up this unstable slope as fast as we could go, and reached the western edge of the summit rim exactly at mid-day. The crater was nearly filled with smoke and steam, which drifted about and obscured the view. The opposite side could scarcely be perceived, and the bottom was quite concealed. As the vapours were wafted hither and thither, we gained a pretty good idea of the general shape of the crater, though as a whole it was not seen until night-time.

A few minutes after our arrival, a roar from the bottom told us that the "animal" (Carrel's term for the volcano) was alive. It had been settled beforehand that every man was to shift for himself if an eruption occurred, and that all our belongings were to be abandoned. When we heard the roar, there was an "it's time to be off" expression clearly written on all our faces; but before a word could be uttered we found ourselves enveloped only in a cloud of cool and quite unobjectionable steam, and we concluded to stop.

The establishment of the tent was the first consideration. It was unanimously decided that it was not advisable to camp at the top of the slope, close to the rim or lip of the crater, on account of wind and the liability to harm from lightning; and the more I examined the slope itself the less I liked it. It was naked, exposed, and slipped upon the slightest provocation. Jean-Antoine and I therefore set out on a tour to look for a better place, but after spending several hours in passing round about a quarter of the crater, without result, we returned to the others, and all hands set to work to endeavour to make a platform upon the ash. This proved to be a long and troublesome business…

When night fairly set in we went up to view the interior of the crater. The atmosphere was cold and tranquil. We could hear the deadened roar of the steam-blasts as they escaped from time to time. Our long rope had been fixed both to guide in the darkness, and to lessen the chance of disturbing the equilibrium of the slope of ash. Grasping it, I made my way upwards, prepared for something dramatic, for a strong glow on the under sides of the steam-clouds shewed that there was fire below. Crawling and grovelling as the lip was approached, I bent eagerly forward to peer the unknown, with Carrel behind, holding my legs.

The vapors no longer hid any part of the vast crater, although they were still escaping. We saw an amphitheatre 2300 feet in diameter from north to south, and 1650 feet across from east to west,1 with a rugged and irregular crest, notched and cracked; surrounded by cliffs, by perpendicular and even overhanging precipices, mixed with steep slopes—some bearing snow, and others apparently encrusted with sulphur. Cavernous recesses belched forth smoke; the sides of cracks and chasms no more than half-way down shone with ruddy light; and so it continued on all sides, right down to the bottom, precipice alternating with slope, and the fiery fissures becoming more numerous as the bottom was approached. At the bottom, probably twelve hundred feet below us, and towards the centre, there was a rudely circular spot, about one-tenth of the diameter of the crater, the pipe of the volcano, its channel of communication with lower regions, filled with incandescent if not molten lava, glowing and burning; with flames travelling to and fro over its surface, and scintillations scattering as from a wood-fire; lighted by tongues of flickering flame which issued from the cracks in the surrounding slopes…

Revista Campo Abierto No. 9, Julio de 1986

Augusto Nicolás Martínez (Ambato, 1860 - 1946). Scientist, climber, farmer, researcher and educator.

Our good friend Manuel María Bucheli will be mad if I say that he is so badly mountaineer as an unbeatable friend and an extremely skilled mechanic? I will not do it, surely, since not being a good mountaineer or taking away or making a king, nor diminishes in an apex his good clothes. But, God bless me! Was not he who, against all the rules of mountaineering, put the idea of making the first stage of the trip on his bicycle? Was not he the one who carried as much impediment as if we went to the North Pole? Did not he carry a famous "Primus" stove of great volume in which the water did not boil in 40 hours, and a carbide lamp that shattered before rendering any service, and appliances for everything and tools for something... ? It was not he who experienced superstitious terror when he saw the fire of Cotopaxi eruption on the eve of the ascension, and he fell on his knees and raised his hands to the sky, exclaiming: "My grandmother will climb it".

On December 30, at 7 o'clock in the morning, we started riding astride our bicycles. At 11 we arrived at Machachi, nothing had happened worth telling. If I did not fear to tire you, I would describe our friend Bucheli in an irreproachable costume of a cyclist and carrying in an artifact of his invention, subject to the bicycle, more than a hundredweight in tools and tools enough to set up a workshop for mechanics, the good ones, that produced such a roar that people moved away as if passing a bus...

... At two o'clock we arrive at a place where the ground no longer rises but, on the contrary, begins to descend sharply in front of us. We are thus on the edge of the crater. Confusingly I understand and try in vain to overcome the confusion that produces me so unusual show. That is chaos. As we cast our glances into the mysterious abyss, we suffer a disappointment, for everything was covered with dense gases that prevented us from seeing anything even of the monstrous den. We only sense something immense, something without a bottom, since the stones thrown inwards don't send any sound, as if they fell into an endless abyss. At times we see the abrupt, almost vertical slope, and in it huge smoking cracks that disappear instantly, as if they were a Dantesque vision or a nightmare.

Nevados de Ecuador y Quito Colonial, Ángel N. Bedoya Maruri, 1976

Cotopaxi Volcano crater

The Geological Institutes of Poland and Czechoslovakia prepared trained personnel for two years to travel to our country and investigate and collect samples of Cotopaxi inside and out in order to reconstruct the most recent classical volcanic development, since Europe and Asia the volcanic terrain it's old and doesn't exceed three thousand meters above sea level.

The expedition consisting of two Poles and eleven Czechs including a woman Cabina Zoubkova was in Limpiopungo the first days of July; during one month they made recognitions, they ascended by three times to the top of the volcano but the unfavorable weather did not allow the descent to the crater, until on September 2, 1972 the unprecedented feat was achieved by two Poles: Andrzej Paulo and Jerzy Dobrzynski and a Czech Bedrich Nicolch.

The story of the scientific episode made Andrzej chief of operations and his compatriot Jerzy, the first to descend to the crater; It was published in the Vistazo magazine whose pages we transcribed:

The inspection of the edge of the crater was not easy. There was permanent fog and wind and only two occasions and for a few minutes we could contemplate the crater in all its magnitude. They also bothered the fumaroles of gray white smoke that are flowing permanently from the bottom but that when going out in the open air changes of direction according to it arranges the wind. This smoke is a hot fluid that has dangerous gases for a living being, such as sulfuric acid and sulfur dioxide plus carbon dioxide. Of these, two have formed a layer of volcanic sulfur in part of the walls of the crater.

The crater, as a whole, when we could see in fullness, gave us a severe, frightening sensation with its pale yellow color and its whitish fumaroles in constant threat.

… On the first day of September, at 10 pm (eight in the evening), the final climb to the top of Cotopaxi began, we were eight men ready to finish the task. We arrived at the crater at dawn the next day; that is to say on September 2. There was an hour of clear weather, in that time we selected the site where we had to install the descent equipment , which is also a special team. I, as the chief of operations, had to stay up, attentive to everything, while my Polish companion went down in the first place.

I started to descend at eleven o'clock in the morning ( Jerzy ); I had the oxygen capsule on my back and the radiotelephone device in my chest. I was tied to a rope and slipped into another rope that had previously been thrown into the void. The visibility, at the beginning was about ten meters; further down there was more clarity and I could even see the opposite wall of the crater, about two hundred meters away.

I was informing my colleagues, above, everything I saw and what I could touch. This, psychologically, was very important for me and also for them. I descended without complications about 120 meters. At first the perpendicular descent but then it was tilted until I could practically stop. At one point I lost my balance and shouted; but it was a small scare because I had fallen into a small hollow one meter high. For me these moments were dramatic. My breathing was a bit accelerated but I did not need oxygen.

Twenty minutes later my Czech companion came down and between the two of us we started the excursion through the crater. We helped each other, to avoid any useless risk. So, if he was to take the temperature of the fumaroles with a thermometer attached to a long rod, I had him assured. If I collected rock samples, he took care of me. And all the time we reported above everything we saw or palpated. There was a single moment when my partner shouted and said a thick word in Czech, they heard it up too. It was that he had rested a hand on a hot rock, and burned a little. At another time a fumarole came on us and we had to put on our gas masks. For the rest, we avoided these columns of smoke because of their characteristic smell. We take pictures in 6x6 colors and in 35 mm. Also the cameraman took a movie from the edge, which we hope will turn out well.

The operation lasted six hours and ended with the placement of the flags of 'Poland and Czechoslovakia on the edge of the crater. The rise of the two companions to the edge of the crater was much more difficult than the descent because they had to overcome a kind of ice tongue that offered many difficulties. The Czech expeditionary hurt his hands on this climb. When they left the crater, the eight men embraced excitedly. That same afternoon, almost at nightfall, we began to descend to our general camp, with our equipment and ten kilos of rocks collected in the bowels of the Cotopaxi ... We have repeated the trip that the Polish professor Siemiradzki made in 1874; he investigated the lavas of Cotopaxi inside, we have completed the task.

Revista Montaña No. 17, February 1994

Yanasacha wall, Cotopaxi Volcano

A page in the history of Ecuadorian Andinism, was written on May 1, 1989, when members of the Club Andinismo Engineering of the Central University, opened a route on the eastern side of the Yanasacha wall, Cotopaxi Volcano.

Let us note that the illusion, long cherished by these mountaineers, was successfully crowned after various obstacles, besides that the aforementioned wall was coveted in recent times by the best mountaineers in the country, which makes this fact more meritorious.

The project to crown the volcano climbing directly on the YANASACHA wall was an objective that had been proposed for some time, for which the training, analysis and observation of the possible alternatives were planned by the members that participated in this expedition, which came to happy completion in the first May, as a tribute to the Ecuadorian worker.

The expedition was integrated by: Edison Salgado (Chief), Jorge Penafiel, Eduardo Agama, Danilo Mayorga, Lesslie Lopez, Roberto Jimenez, Oscar Villacis, Sandro Celi y Rudy Chain (Cameraman).

The indicated mountaineers left from the Refugio Padre José Ribas, on Saturday at 09h00 to make a high camp at the base of the wall at 5,700 m. , after a long and painful ascent, due to the snow loose route, bad weather, and the heavy backpacks they carried on their backs.

On Sunday very early, after a comforting rest, 4 climbers go out to equip the route in its stretch of rock, at 08h30, they start working on it. Jorge Peñafiel punches the first two lengths of string, to continue Eduardo Agama with the third length of string, the fourth string length is done again by Jorge Peñafiel, having finished the rock work at 2.30 pm they decide to return to base camp , for the next day, make the final attack.

The work done, this day was very difficult since it required a lot of precaution, technique and proper use of rock climbing equipment, due to the very unstable volcanic material with rock and sand detachments, in addition to a persistent snowfall and the prevailing cold.

On Monday, May 1 at 07:30, they begin to climb the fixed ropes placed the previous day, arriving at the glacier at 10h00, when Edison Salgado, continues the climb on the final stretch of the wall, consisting of two lengths of rope in ice and snow.

If the rocky section was difficult, not least was this part: plates of ice and snow, very steep walls of up to 90 degrees, where the use of ice material was very frequent. Finally it's possible to climb the ice layer above YANASACHA, at 2:00 p.m. and then continue to the summit of the volcano , at 2:30 p.m. the descent to the base camp and the refuge begins.

The climbers who made this first ascent are: Edison Salgado, Jorge Peñafiel, Eduardo Agama and Danilo Mayorga, who baptized this route as: “LA RUTA DE INGENIERIA”.

Deportes sin Limite Magazine, July 1998. Author: Gabriel Llano.

I remember that after writing a letter to the gentlemen of Deportes Sin Límite, I left with a bad taste in my mouth when claiming and encouraging, but not giving practical examples, about the new routes that can still be done in the country. So, after attending the Mountain Guides graduation, event that summoned many climbers in the middle, I was captivated by the illusion of returning to Cotopaxi to try to get us to close the chapter of the route of the North-East Ridge.

Then the next day, after surviving a tenacious bottleneck at a friend's house, we left in the morning towards the hill. We were: Gaspar Navarrete, Jurg Arnet and who writes this short story; Oswaldo Freire had to accompany us, but unfortunately - he says that despite his opposition - he could not get rid of the aforementioned bottleneck.

With the tachycardia to the maximum degree and the hairs of tip, product of dodging the potholes and exceeding to the gentlemen buseros that only went to 140 km. per hour, our gentle friend Jurg took us in his white exocet to the parking lot of El Coto, at 4600 m. of altitude.

Once in the shelter, after ingesting more than a liter of valerian water to settle the nerves, we checked the equipment for the umpteenth time and at 3:15 p.m. we left with an eastern direction, that is to say towards the glacier where the internships were carried out. the rookies prior to the promotion. From there we had to cross three more edges, which implied a new passage through the sand before entering the glacier. At around 7:30 pm, at an approximate height of 5070 m. we installed the bivouac.

Achachay, how cold! At 03:00 we raised the bivouac and left. Due to the good smell of the three of us we managed to get out to a crack that seemed to destroy the illusion of reaching the summit, but thank God, who takes care of their animals, we found an unstable and precarious step, however, I pass at the end. A couple of more cracks with vertical outlets and a last one that had a wall of more than 20 m. of loose and unstable snow that made it really not easy at all. Overcoming this delicate sector we headed towards the top domes that were lined with a very deep wind plate in which it's the first time - I must confess - that I am literally crawling on the mountain; nevertheless, my quadruped footprints were not the only ones on the snow, two deep channels marked the winding path traced by the profiled and not short noses of my companions who almost like me were literally nailed to the mountain. This section takes us about an hour and a half, but fortunately it ends and with this the route also ends.

We reached the top edge of the crater at 10h00. We are about seventy meters south of the place where the seismograph of the Geophysicist of the National Polytechnic was installed, and as Jurg tells us in 15 minutes we would reach the summit. What he did not know was that the crest crack is open about two meters and is uneven, so neither intentions remain to become the athlete and jump. Well, we return to the edge of the crater and we drop to the inner ring; We make a crossing and go to the normal route to return to the refuge at 3.30 pm and we meet with our common friend the "good genius" Rojas who proceeds to congratulate us effusively.

As a corollary, comment and suggestion, I say that it's a serious but feasible way, in which one of the attractions is that by not seeing the wall of Yanasacha during the ascension it seems that we are in another mountain.

I suggest starting the first day early in the morning for several reasons: ascend as high as possible, choose a safe place for the bivouac and analyze the route of entry and exit with more time and care to avoid sites of possible avalanches that are many.

Very careful with the state of snow and weather!