Nevados de Ecuador y Quito Colonial, Ángel N. Bedoya Maruri, 1976

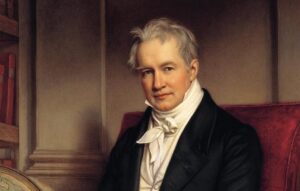

Alexander von Humboldt, by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1781 - 1858, German painter

The summit of Iliniza is one of the most picturesque and majestic of those around the colossal city of Quito. They are divided into two pyramidal points that were probably an ancient volcano, now extinct and has absolute height of 5,202 m. This mountain is located in the western chain of the Andes, parallel to the Cotopaxi volcano. It joins the top of Rumiñahui by the top of Tiopullo that forms a transversal chain through which the waters flow at the same time towards the South Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The pyramids of Iliniza are seen at a great distance from the plains of the province of Esmeraldas.

Carta del Dr. W. Reiss á S.E. Presidente de la República, Gabriel García Moreno

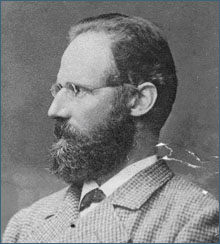

Wilhelm Reiss (13 June 1838 – 29 September 1908), German geologist and explorer

The Iliniza is composed of two different hills: the northern peak seems the oldest, so that the eruptions of the southern peak have largely covered the southern slope of the peak. From these circumstances it turns out that between the two hills there is a saddle that is now filled with the ice-trees that come down from the southern peak . Said saddle is quite wide and since it has an inclination from the East to the West, it forces the ice to descend to the headwaters of the Hondon de Cunteuchu.

Almost all the high hills of the Western Cordillera are very steep and have deep valleys on the western slopes; but Iliniza is the exception to this rule ; so it's easy to ride on horseback through these skirts, while almost inaccessible deep gorges descend to the eastern side, draining into the plateaus of Callo and Machache.

Certainly the Iliniza is one of the most beautiful hills of the south of Ecuador : its isolated position, its great height and the meeting of the two snowy cusps make it stand out among the hills of this mountain range, and a narrow blade, composed partly of ancient rocks [Cruzloma de Atatinqui] and partly of volcanic rocks, it joins it with the Heart; while to the south it extends between the Iliniza and the ancient mountain range of Guangaje and Grintiví, the plain of Curiquingue, in whose skirt is the village of Toacaso.

The ancient formation on which the Iliniza volcanic masses are superimposed extends to the West, forming the forest covered hills that enclose the rivers of Atacamos and Toache, and among those that deserves to be mentioned especially the Cerro Azul, famous for its great wealth of machine The north cusp of the lliniza is composed of thick lava flows of a very particular composition, the lavas don't appear under the appearance of solid and crystallized rocks, but as gaps; I mean, they are lavas of agglomeration or eutaxitas; while; the lavas of the south cusp are compact and well crystallized. As an interesting fact I can mention that in the middle of these essentially trachytic rocks, there are also varieties full of olivine. In short, the Iliniza shows to be an ancient volcano , whose form is already quite altered by the action of the waters; however, some of the more recent lavas still retain the particular and characteristic aspect of the currents of this class. The only hint of the interior heat of the hill are perhaps the thermal waters of Caricunucyacu and Guarmicunucyacu , which sprout at the headwaters of the Blanco river on the eastern slope of the hill.

Travels amongst the Great Andes of the Equator, Edward Whymper

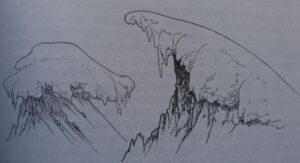

Whymper: different kinds of cornices

In course of time it was found that we had got close to the southern edge of a glacier on the eastern side of the peak, and that the upper 2200 feet or thereabouts of the mountain was composed of a large wall (which is possibly nothing more than a dyke), of no great thickness from east to west; having two principal ridges,—one descending from the summit towards the south-south-west, and the other north-north-east. The face fronting the east was almost entirely covered by glacier right up to the summit, and there was also a glacier, or more than one, on the western side.

Jean-Antoine and I started soon after daybreak on Feb. 9,1 and made good progress over the glacier so long as it was at a moderate inclination; but in the course of an hour we found ourselves driven over to the western side of the mountain, and shortly afterwards were completely stopped in that direction by immense sdraes. We then doubled back to the main ridge, and reached the crest of it, at a somewhat greater height than 16,000 feet, up some very steep gullies filled with snow. The huge semes looming through the mist above us on the western side shewed clean walls of ice which I estimated were 200 feet high, lurching forwards as if ready to fall, separated by crevasses not less than twenty to twenty-five feet across. Nothing could be done on that side. The ridge was steep and broken; its rocks were much decomposed, externally of a chalky-white appearance, pervaded with veins and patches of lilacs and purples, and interspersed with numerous snow-beds overhanging one or the other side in cornices. The thickness of the mists hindered progress, and shortly before mid-day (being then about 17,000 feet above the sea) we were brought to a halt. The clouds drifted away for a few minutes, and we saw that although we might advance perhaps two hundred feet higher we should not be able to reach the summit.

Two glaciers have their origin on the upper part of the southern ridge of Illiniza. That which goes westwards, almost from its commencement, is prodigiously steep, and is broken up into the cubical masses termed s6racs. The other glacier, descending towards the east, though steep, is less torrential. The two were united on the crest of our ridge, and over some cleft in it there was a sheer, vertical wall of glacier-ice perhaps a hundred feet high. We could see no way of turning it, and there appeared no possibility of getting higher upon this side except by tunnelling. But, if we had passed this obstacle we should not have reached the top of the mountain, for its extreme summit was garnished with a cornice of a novel and very embarrassing description. In the illustration at the head of this chapter two types of snow-cornices are represented. That on the right of the engraving is common upon the crests of ridges near the summits of many Alpine peaks, and in other high ranges, including the Andes. The one upon the left I have seen only amongst the Great Andes of the Equator, and for the first time on the summit of Illiniza. We observed them again upon the lower peaks of Antisana, Cayambe, Cotocachi and elsewhere.

The formation of snow-cornices of the more usual type is due to drift of the snow, and the icicles underneath them to the subsequent action of the sun; and the process of their manufacture, upon a small scale, can be observed upon the ridges of roofs during any severe snowstorm. The other type —the tufted cornice—is probably due to variability of winds, and the fringe of pendent icicles, all round, to the influence of a nearly vertical sun at noon. With the exception of Illiniza, they were not found at the very highest points of the mountains which have been mentioned, and we thanked our stars that it was not necessary to have dealings with them.

We descended eighty feet to read the barometer; made our way down the eastern face, and became mist-bewildered on the glacier near the camp. Our shouts were heard by Louis, who pluckily hobbled out some distance to guide us, and we then packed up, and awaited the return of our followers. They arrived at 4.30 p.m., and we quitted a mountain upon which, I don't attempt to disguise, we were fairly beaten.

Our experiences upon Corazon and Illiniza began to open our eyes regarding weather at great elevations in Ecuador. Hitherto we had seen little of vertical suns, and regarded ourselves as the victims of circumstances, circumstances, and looked daily for the setting in of a period of cloudless skies, with something like tropical warmth. On Illiniza we enjoyed thunderstorms, snow and hailstorms, sleet, drizzle and drenching showers, and scarcely saw the sun at all.

At Machachi we met Seflor Lopez, an engineer of the Ecuadorian railway, who said that this weather was in no way exceptional, and would be found alike over all the higher ground, in any month. We resigned ourselves to the inevitable, and set to work perfecting preparations for a journey to Cotopaxi.

Montañas del Sol. Serrano, Rojas y Landázuri, 1994

Augusto Nicolás Martínez: Ecuadorian scientist, climber, farmer, researcher and educator, Ambato 1860 - 1946.

In the morning we can go to the Illiniza. The road is very good and the journey from the Hacienda Puchalitola to the camp, we have traveled in a few hours ... In the afternoon, we planted our tent in the "Enchanted City of Illiniza", located northwest of the southern peak of this mountain and at 3,850 meters high. Many times I had seen this place from the knot of Tiopullo and I was always spickup truck by its appearance as a town or a destroyed city, hence the name... I supposed that I was going to find some accumulation of lava or something similar, but there is nothing of that, but simply fields of white sand shaded by groves of yaguales ... it's very populated; because many rabbits live in it, and it seems that they also visit it, deer, wolves and leopards, judging by the traces of these animals printed in the sand...

Near the summit and when we were sure of the triumph of our company, we were stopped by a vertical wall of 25 meters height and absolutely inaccessible, which separates us from our long-awaited goal...

To reach the mathematical summit, formed by the two pyramidal peaks, separated by a gorge, we are a few meters away, and moments later we tread the virgin summit of the North Peak of Illiniza, which we baptize with the name of "Pico Villavicencio" in honor of the Quito geographer of this surname and close relative of our partner. At the same time, we also baptized the South Peak with the name of another illustrious sage, honor of Ecuador, Mr. Pedro Vicente Maldonado.