Travels amongst the Great Andes of the Equator, Edward Whymper

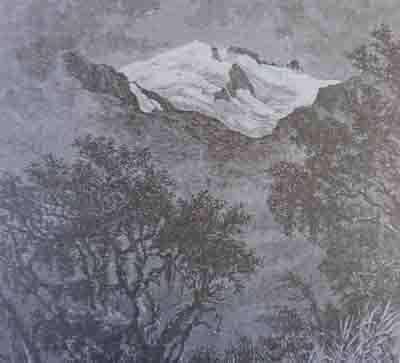

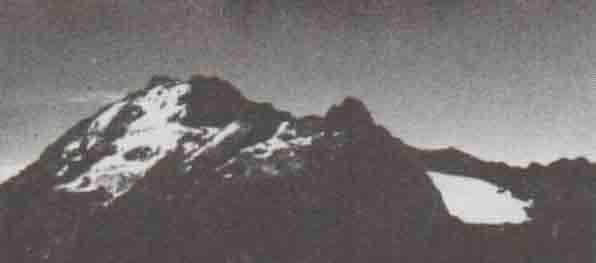

Saraurco, conquered by Edward Whymper in 1880

April 17. Ascent of Sara-urcu. Left Corredor Machai at 5.30 a.m. Foggy. Went as before across the valley, a little to the north of east. Rain fell 6 to 8 a.m. Passed camp on Sara-urcu at 8.55, picking up necessaries which had been left there in readiness. Then steered east; rounded the slopes of the ridge bounding the southern side of the large glacier proceeding from our mountain, passed the base of a small lateral glacier and took to the ice at 10.50 a.m. Put on the rope. Could not see a hundred yards in any direction. Steered eastsouth-east.

The summit of Sara-urcu bore almost exactly due east from Corredor Machai, and an east-south-east course was calculated to bring us right upon it. To return steering by compass was more dubious. We did not apprehend losing ourselves on land; nor upon snow and glacier, even in a fog, if our track was not obliterated. There was every probability that it would be quickly effaced; while it would be necessary, to escape from the glacier, to hit off the exact place where we took to it. It was by no means certain that we could do this, trusting to the compass alone; for it's very difficult to hold to one general course in a fog, when courses have to be changed every other minute, as they must necessarily be upon crevassed glacier.

Luis therefore brought a large quantity of reeds, cut four feet from its top, to place as guides on the glacier and planted another as soon as the last one he had fixed became dim. While this scarcely hindered progress, it allowed us to proceed with greater confidence. We rose steadily, crossing many crevasses; and when about 15,000 feet high suddenly emerged from the clouds, and found ourselves face to face with the pointed snow peak. Behind this, a wall of snow led to the true top.

With out-turned toes we went cautiously along the crisp arete, sharp as a roof-top, and at 1.30 p.m. stood on the true summit of Sara-urcu; a shattered ridge of gneiss—wonder of wonders, blue sky above—strewn with fragments of quartz, and micaschist similar to that at Corredor Machai, without a trace of vegetation. The usual atmospheric conditions prevailed. Cayambe and all the rest was shut out by unfathomable, impenetrable mists, limiting the view to a few hundred yards around the summit, which was surrounded by glaciers on all sides. Temperature rose and fell as puffs of steamy air came from the great cauldron on the east. The barometer stood at 17.230 inches, and thus it was clear that Sara-urcu was not the fifth ally from the statements made about that mountain by Villavicencio. He gives in his Geografia 6210 varas as its height; upon his map, places it south of east of Quito and south-south-west of Cayambe (mountain), near Papallacta; he quotes from Velasco to the effect that it was a volcano which formerly emitted fire, and he says it has latterly ejected ashes, producing consternation in the Capital, whence it's distant thirty-five miles. I found that Sara-urcu is only 15,502 feet high, and is placed south-east by south of Cayambe (mountain); that it's not a volcano, and cannot have emitted fire and ejected ashes; and that it lies considerably to the north of east of Quito, at the distance of about forty-five English miles. Instead of being the fifth in altitude of the Great Andes of the Equator, it proved to be the lowest of all the snow-peaks, and considerably inferior in elevation to several which scarcely reach the snow-line.

Campo Abierto Magazine, No. 15, authors Jack Bermeo and Jorge Larrea, 1992

Saraurco, first Ecuadorian conquest in 1955

Of medium height, sturdy build with a hoarse and high-sounding voice, he was an innate talker, full of anecdotes: terror monopolized attention, comedic caused hilarity. This cheerful and optimistic personality, with so many experiences in his life, was our companion, dear "old" Miguel Angel Quijano, his name well put, Angel, because he had a white soul. He worked in Cayambe; but he found ways to attend the weekly New Horizons meetings. He knew a lot about the eastern jungle and he always had an obsession that finally expressed it within our group: ascending the Saraurco.

He had it all planned; His enthusiasm convinced us and we decided to go to the mountain on the November holiday, in this case, in 1955.

One week before the date set for the expedition, Miguel Angel hired guides in Cayambe, porters and mules for the approach. Thus, on October 28, very early in the morning, the expeditionary group left the group's premises in the jeeps of Jack Bermeo and Joaquín Borja to the hacienda el Hato , located in the vicinity of Cayambe, where the porters loaded our equipment on the mules, leaving for the east at around 9:30 am. We walked until sunset and set up our first camp in a wheat stubble where we took advantage of the straw to soften the ground.

The next day, Saturday 29, a long day awaited us. We get up very early; but Paco Tobar García, tucked into his cover, slept peacefully, oblivious to our movements. The good humor was not lacking: Jack placed on the floor next to Paco's face a perfect rubber imitation of human manure, which he moistened with hot and steaming water to give it more realism ... Paco, Paco, wake up, they told him, shaking his shoulder. You can imagine the blasphemies he yelled when he opened his eyes and saw it so close to his nose. The more he insulted, the more laughter he produced, Paco's anger was taking on serious characters until Jack withdrew the imitation and put it away in his backpack, to the surprise of our enraged friend.

After a good breakfast, we started the march at six in the morning in the direction of the hut that a "gringo" search engine had built gold, in the middle of the jungle, which we reached at sunset. We camped there without much incident. The next day we loaded our equipment with the help of the porters, because the mules could not continue. After a long jungle road, we descended to the Volteado river, the same one that we crossed several times; the path was covered with "bulrush" , grass with long, thin leaves with silicous and sharp edges, a favorite food of the tapir, as our custom was to walk in shorts, we resulted in many cuts in the legs. After crossing a long beach we went up to the big "machay", a place we arrived at around 4:00 pm . The guides and porters settled in the cave, we adapted a place to stop the big tent of Manuel Yánez. Joaquín was in charge of preparing the typical colada de máchica, which only after the third attempt came out in due form since in the first two he was burned because he was more attentive to the conversation than to the kitchen. On Monday 31st, the group of mountaineers made up of Jack Bermeo, Jorge Ponce Herrman, Joaquín Borja, Jorge Larrea, Oswaldo Mantilla, Manuel Yánez, José Punina, Francisco Tobar, Alfonso Mera, Eduardo Parra, Ignacio Schrekcinger and Miguel Angel Quijano, head of The expedition, we left for the mountain.

Upon reaching the base of the snow, Eduardo Parra decided to stay to take pictures and then return to the camp that was in sight. As we were informed that the Saraurco had no snow, some companions did not bring their crampons, forcing us to divide into two groups to overcome the glacier.

The first group reached the summit at 12:15 p.m. and left a message on it, inside a glass bottle, as proof of the ascent that was the second to this summit, after Whymper's in 1880. We baptized this summit of 4710 m as "New Horizons"; "Asunción" the southern peak and "Quijano" the western one.

Once the first group reached the summit, we descended and loaned our crampons and snow goggles to those who stayed, but Even so, there was a lack of resources for Paco, who, crying, said that in his life he had had two disappointments: the first, when his girlfriend got married and the second, this, not having brought equipment to ascend the Saraurco. Faced with this situation, Joaquín, who served as the guide for the second group, went up for the third time, accompanying our dear friend Paco, who was singing his familiar song while ascending:

it's because of Dolores's legs that the gentlemen They can't sleep.

When we returned to the camp, around 4:30 p.m., we numbered ourselves and to our surprise we realized that Eduardo Parra was missing , so we decided to return immediately to the mountain, dividing ourselves into groups to give more coverage. With the last rays of the sun and when we had raised the highest blades, Eduardo responded to our screams from another blade very far away, where we could see him standing on a large rock.

We quickly descended the huge ravine formed by the dragging of glaciers. Before dark and when we joined him, he cried with emotion and told us that when he felt lost, he knew that his companions would come back to help him. Eduardo, intelligently, instead of descending, he ascended and positioned himself on that high rock so that we could see him. If on the contrary, he had descended into the jungle, it's possible that today we would not have him.

At dusk we returned to the camp and the next day we returned to the gringo's hut where we arrived. With great enthusiasm, because with much foresight, we left for the return a good portion of potatoes to cook them and a tasty cake, to celebrate the success that we sensed our expedition was going to have, but the hunger was so great that it seemed like little flavor.

On Wednesday 2, we were already feeling fed up with the mountains, we decided to return in one day to El Hato , where we left the vehicles. The walk was hard and long; Oswaldo Mantilla couldn't take it anymore and we had to take turns supporting him and practically carrying him on our shoulders.

The guides and porters commented in amazement about our ability. The guides were called: José Caguango, Reynaldo Chicaiza and José Antonio Velásquez, and the porters: Virgilio Jiménez, Rafael Rivera. Luis Landeta and Esteban Sarche; that is, the expedition was made up of 12 climbers from Nuevos Horizontes and 7 between guides and porters, that is a total of 19 people.

Before returning to Quito we celebrated in Cayambe with some beers and a good meal, satisfied by the success achieved by our club and by the companionship and solidarity friendship shared among all during this unforgettable expedition.

Take this opportunity to express once again our sorrow for the disappearance of the dear and remembered colleagues Miguel Angel Quijano, Oswaldo Mantilla and Ignacio Schrekcinger.