Travels amongst the Great Andes of the Equator, Edward Whymper, Edward Whymper

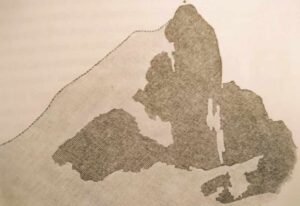

Sincholagua Summit, drawed by Edward Whymper

The ascent of Cotopaxi, however, was considered severely scientific by my men. Prolonged residences in exalted situations were little to their taste. They pined for work more in harmony with the old traditions; for something with dash and go,—the sallying forth in the dead of the night with rope and axe, to slay a giant; returning at dusk, with shouts and rejoicing, bringing its head in a haversack. I sacrificed a day to meet their wishes, and told them to select a peak, just as one may give a sugar-plum to a fractious child to keep it quiet.

Giants were scarce in the neighbourhood of Pedregal . My men looked upon Pasochoa with a sort of contempt, and at Ruminahui with disfavour, as there were at least half-a-dozen ways up it; and their choice fell upon Sincholagua, an attenuated peak, appetizing to persons with a taste for Aiguilles, that had stared us in the face when we looked out of the window at Machachi, which might be ascended in one way, and in one only.

As Sincholagua promised to give full occupation for a day, it was arranged to ride as far as animals could be used; and we should have started before sunrise, only, when the right time came our mules were nowhere, or, speaking more correctly, they were everywhere, as the arrieros after carefully driving them into a yard where there was nothing to eat had left the entrance to it unclosed, and the animals very sensibly wandered out on the moorland, where they could browse.

We sallied forth on Feb. 23, at 7 a.m., and after returning a few miles over the Cotopaxi track turned sharply towards the east, directly towards our mountain; crossed the tiny Rio Pedregal and some moorish ground, and at 8.15 forded the Rio Pita…

At about the height of 14,800 feet our animals could go no farther, and were left in charge of Cevallos. This spot was just above the clouds which are underneath the summit in the engraving on the opposite page. All the grass land was below, and we were confronted with crags, precipitous enough for any one, crowned by fields of snow and ice, the birthplace of a fine hanging-glacier which crept down almost perpendicular cliffs, clasping the rocks with its fingers and arms.

We tied up and stopped northwest over some ragged ground. The manner of approach had been settled beforehand. The south side of Sincholagua was inaccessible; inaccessible; garnished with pinnacles like the teeth of a saw, and terminated at the immediate summit by sheer precipice. The western side was equally unassailable, and the only way by which the top might be reached was from the north, along the snow arete at the crest of the mountain.

In two hours we rose more than another thousand feet, and (having turned sharply to the right and climbed the snow on the left of the engraving) passed under the cliffs of the minor (northern) peak. We were nearly sixteen thousand feet high, with a clear sky, and the summit not far off; men in good spirits, rather inclined to crow, and to vaunt the superiority of the old style, when—Heaven knows where it came from—a hailstorm sent us flying for protection to the cliffs, crouching in their fissures, covering our faces with our hands to save them from the half-inch stones which bounded and ricochetted in all directions, and smote the rocks with such fury that they dislodged or actually broke fragments from the higher ledges. Twice we left our refuge and were beaten back. These ice-balls were as unpleasant as a shower of bullets.

Then came a lull. Snow began to fall, at first mixed with the hail, and afterwards in large flakes, thickly. The hail ceased, and was succeeded by lightning. Emerging from our retreat, we traversed the glacier to a small island in its midst,1 and stormed the slope banked-up against the wall which forms the summit ridge, and found the drifted snow along its crest surmounted a sheer precipice on the eastern side. The narrow way along the top led to the foot of the final peak. The route could not be mistaken, though the summit was invisible and our acete, rising at an increasing angle, disappeared in the thunderclouds.

Hitherto the flashes had only glanced occasionally through the murky air, each followed by a single bang, which is all one hears when close to the point of discharge.1 Around the peak they blazed away without intermission, several often occurring in a single instant. The whole air seemed to be saturated with electricity, and the thunder kept up an almost continuous roar.

With ice-axes hissing ominously, and confined to the crest of the ridge by the abruptness of its sides, we gradually approached the summit. The last few yards were the steepest of all. The snow was reduced to a mere thread (too small to be shewn in the annexed engraving2), leaning against the rock, and it was marvellous that it stood firmly at such an angle. Steps at an ordinary distance apart could not be made. The leading man stretched forward to scrape away a small platform, flogged it down to make it cohere, then dashed his axe in as high as he could reach and hooked himself up, while number two drove in his baton as far as it would go to prevent the snow from breaking down. In this manner we arrived at the summit. Its top was too small to get upon, and, by exception, was solid, unshattered rock right up to its very highest point. Jean-Antoine knocked off its head with his ice-axe whilst I operated a few feet below.

Having performed this important ceremony, we immediately descended, face inwards for the first part of the way, with lightning blazing all around as far as the end of the summit ridge. Then it ceased; we ran down to Cevallos, and, driving the beasts before us at a trot to the bottom of the slopes, recrossed the Rio Pita higher up than before, and pushed the pace hard all the way to Pedregal.

The giant was slain, and we returned, rejoicing, with its head in a bag…

Revista Montaña No. 31, written by Hugo Torres

Sincholagua as it was, covered with glaciers, now it has lost all of them

I had the opportunity to climb the second summit in importance, the southern summit, in August 1974. I did it together with my great friend Miguel Andrade, one of the great climbers that our country has given, and with whom I also had the opportunity to ascend other virgin peaks, among which the eastern peak of Antisana stands out. That ascent was born as all the ascents to the virgin summits of our Ecuador have been born: simply by the desire to do so. That was a time of great conquests, of healthy sports competition, led above all by the San Gabriel School and the Andinismo Club of the Escuela Politécnica Nacional.

Together with a group of dear friends -Marcelo Asanza, Patricio Hoyos, Erica Elliott and others who now escape from my memory- we decided to face the challenge. We all take the heavy climbing equipment to the base of the mountain, where we arrive through Limpiopungo , crossing and ascending the paramos to the southwest of the mountain. Once located at the base of the rocks, we ascended to the right by a salient channel of sand that took us to a terrace at the foot of a rocky outcrop. There we realized that the thing was not as simple as it seemed when looking at it from afar. We looked towards both sides of the rock wall, which was almost completely overgrown, until finally we found the "Achilles' heel" of the cliff: a small fissure of approximately ten meters that descended from the top to the very base of the rock wall. We soon told bye to our friends, and there, for that almost imperceptible crack, the first of us climbed.

I have always admired the innate qualities of climber Miguel Andrade has. That day, like many others, he stuck his fingers in the fissure as if they were cat nails, placed the nuts and the pythons, and little by little it was gained height until disappearing on the upper edge. The rope tensed and from above Miguel told me that the rope was ready to go up. I followed in his footsteps with the assurance that I knew I was protected from above, and soon I arrived at his side.

What a beautiful show! At our feet the overhanging rock wall and in front the magnificent snow cone of Cotopaxi; upwards, over our heads, a tangle of rocks and stony walls that did not look bad. It was my turn to continue opening the climb rock after rock, wall after wall. With four more lengths of rope we finally left towards a wide terrace of stones and sand to run into another cliff, which we attacked with relative ease. Finally, a large inclined triangle of sand took us directly to the summit. It was only 3 or 4 in the afternoon, so we were filled with the pleasant tranquility of having finished a well done job. We decided to baptize the peak with the name of a distinguished professor of the National Polytechnic School, Dr. Bruce Hoeneisen, one of the pioneers in introducing modern rock climbing techniques in Ecuador in the 1970s.

Although we descended as fast as we could, the threshold of the night reached us when we finished rappelling the first of the walls that we had ascended many hours before. With lanterns we managed to lower the sand gutter and when we reached the páramo we decided to end the day. We were tired and we deserved a good sleep. Also, the night was beautiful and our friends had already seen us, so there was no worry.

Very early the next morning we heard noises around us: there were our companions with hot tea, some delicious sandwiches and, above all, that great affection that always joins us to the mountaineers.

Approaching the highest summit, 1974